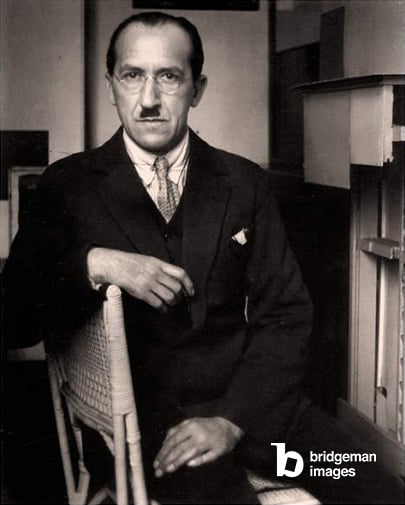

Piet Mondrian - Art from the Spiritual Realm

There are few artists that can be considered to have the same level of importance in the 20th century than Piet Mondrian. Many of Mondrian’s images have become synonymous with our understanding of Modernist Art, and in many ways, he is the perfect example of the modern artist, due to his utopian ideals and abstracted form.

For many, Mondrian is most notably remembered for being a leading figure in the Modernist fight towards abstraction, a form determined to discard the need for representation and narrative in painting, to achieve an art that communicates on a plane beyond our conventional conceptions of reality, one that is determined to discover the truth behind visual appearance and nature.

‘I want to come as close as possible to the truth and abstract everything from that, until I reach the foundation (still just an external foundation!) of things…’

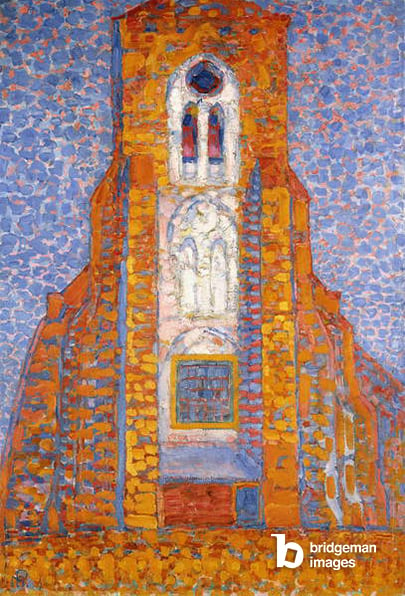

Born in the Netherlands, Mondrian developed an interest in art from a young age and grew up to study at the academy for fine art in Amsterdam. Here he worked in a naturalistic and realistic style, alike the other post-impressionists of the period. In these early years his subjects consisted of landscapes populated with pastoral imagery depicted using a mix of earthly colours.

In the first ten years after the fin de siècle we witness a shift in Mondrian’s palette which changes to predominantly include primary colours and the subjects form begins to be less identifiable, gradually becoming more consumed by the thick brushstrokes and their vibrant colours.

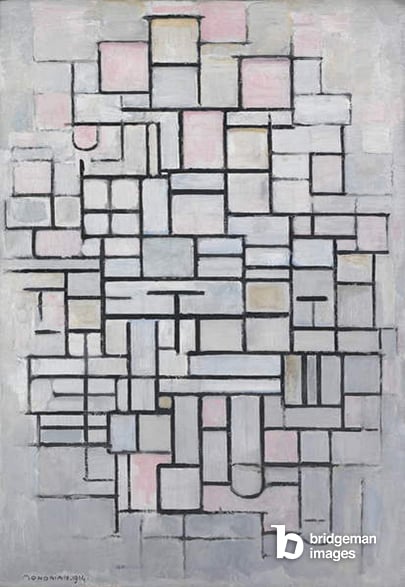

The first major revolution in Mondrian’s style came in 1911 after witnessing the works of prominent cubists Picasso and Braque at the Moderne Kunstkring exhibition in Amsterdam. Following this and his move to Paris, Mondrian’s paintings began to be more fragmented, as they were extinct of any identifiable subject matter and the picture plane was split up into an array of quadrilateral segments.

In the years during the war, Mondrian became stricter with his use of colour, only deploying primary colours that were prevented from mixing. Around the same time Mondrian grew close to other artists including Van Doesburg who was working in a similar style, and together they founded the de Stijl group and Mondrian began to publish his theories on Neoplasticism, laying forth a new doctrine for visual art.

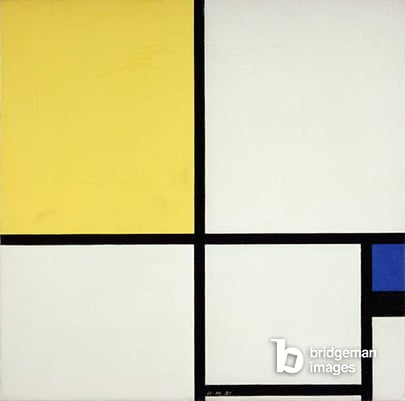

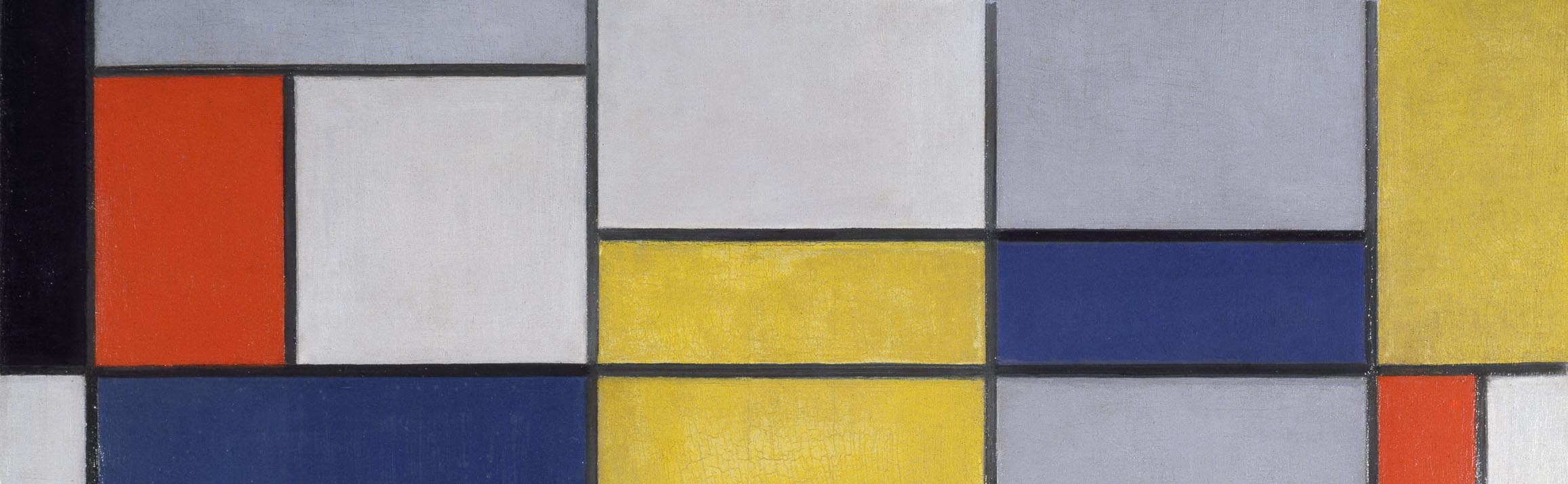

The theory confirmed Mondrian’s concern with elevating the properties of art, claiming that it had an almost scientific ability and duty to become a ‘pure representation of the human mind’, expressed in an aesthetically purified abstract form, ‘in the straight line and the clearly defined primary colour’. From this arose Mondrian’s most distinctive style and works which began in the 1920s and spanned the rest of his life.

These ‘compositions’ appear as a series of endless variations of the same theme through numerous works. They are all inhabited by asymmetrically fixed square segments of colours, that are divided by vertical and horizontal lines, changing in length and thickness. Each composition feels perfectly constructed although completely arbitrary and random. Is this a perfect reflection our existence?

In every case, Mondrian explained that his art was driven by a desire to express and explore something spiritual. He believed art had the ability to transition to other dimensions, or what he called the ‘spiritual realm’. In many of the paintings of this time we can feel this complete harmony and equilibrium within their arrangement and the spaces that seem to be between the inhabited and the ones that are void.

In some paintings the abstraction is so extreme that most of the plane has become consumed with white paint and the pockets of colour become secondary and squeezed of the canvas, forcing the viewer to ponder these arrangements and the relationships between colour, line and space.

Prior to world war II and due to the rise of European fascism, Mondrian moved to London and then crossed over to New York City in 1940. With the support of his friend Peggy Guggenheim, Mondrian was introduced and accepted into the New York Avant Garde art scene and joined the American Abstract Artists.

It was at this time, amazed by his new environment that Mondrian’s work became influenced by the construction and vivacious energy of the metropolis. This caused him to abandon his black grid, favouring double and coloured lines that where animated by coloured squares, resembling the dazzling lights and music he experienced within the city, evident in his piece last unfinished work ‘Victory Boogie Woogie’ made in 1944.

Entirely dedicated to his work, Mondrian remained unmarried for the whole of his life, reflecting the purity and discipline of his art and in 1944 died at the age of 71. The abstraction and utopian ideals of Mondrian’s vision and art has had an insurmountable impact on the course of modern art. Notably they have been a source of reference and inspiration for the Bauhaus and later movements including minimalism and constructivism, as well as being used as a source for many post-modern and contemporary projects. Mondrian may be gone but his abstract, utopian vision for art still manages to intrigue and fascinate many of us today.

‘led by high intuition, and brought to harmony and rhythm, these basic forms of beauty, supplemented if necessary by other direct lines or curves, can become a work of art, as strong as it is true.’

Discover all of Mondrian's work and related images on the Bridgeman Images Archive.

Read More