Impeccable Originality: The Artistic Influence of El Greco

Doménikos Theotokópoulos (1541 – 1614), commonly known as El Greco, or The Greek, although born in Crete, is hailed as one of the pillars of Spanish Renaissance painting. But it wasn’t always that way…

Commemorating the 400th anniversary of the artist’s death this November, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in partnership with the Hispanic Society of America, is hosting a retrospective show of El Greco’s most ground-breaking works, examining his influence on generations of artists.

Early Criticism

El Greco’s stylistic paintings were said to be too “individual” for his time to be placed in any conventional school or movement. Attempting to express religious emotion in his works, El Greco’s jarring “acid” palette, elongated anatomy, irrational perspective, and obscure iconography display key aspects of Mannerism,a style of 16th-century Italian art. Shunned by the critics of the day due to his opposition in technique to the accepted Baroque style, the works of El Greco were also scorned by the immediate generations after his death.

“I hold the imitation of color to be the greatest difficulty of art.” – El Greco

Jesus Driving the Merchants from the Temple / El Greco (Domenico Theotocopuli) / Church of San Gines, Madrid / Bridgeman Images

Later Admiration

In the late 18th century, literary critics re-examined El Greco’s work in a new light. Esteemed French writer Théophile Gautier saw El Greco as precursor of the European Romantic movement, the “ideal romantic hero”, and opened the doors for admirers to re-evaluate the artists’ masterpieces.

In the early 1900’s, El Greco became immensely popular amongst budding Impressionists who had traveled to Spain to explore new influences. His supposed “complete indifference to what effect the right expression might have on the public” appealed to the rebellious Impressionists who respected his unique style as being ahead of the curve, in contrast to earlier critics who thought the exaggeration in his biblical works were due to mental or physical illness.

Adoration of the Shepherds / El Greco (Domenico Theotocopuli) / Museo del Patriarca, Valencia, Spain / Bridgeman Images

Édouard Manet

The expressive colors and vibrant mark making and even compositions evident in any El Greco painting seemingly had a great influence on the works of Edouard Manet.

Paul Cezanne

French Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cezanne was one of the first artists to be critically linked to the influence of El Greco, attributing his early impressionist themes to the late artist. Comparisons between the two artists’ color pallets and human forms are often made.

“… Renoir and Cézanne are masters of impeccable originality because it is not possible to avail yourself of El Greco’s language” – Julius Meier-Graefe, 1908, The Spanish Journey

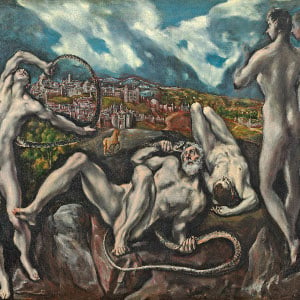

Laocoon / El Greco (Domenico Theotocopuli) / National Gallery of Art, Washington DC / Bridgeman Images

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso further explored El Greco’s cubist influence, playing on El Greco’s distorted and elongated forms to the extreme. Picasso often explicitly exhibited comparisons to El Greco’s work in stylistic copies of the late artists well known works.

“In any case, only the execution counts. From this point of view, it is correct to say that Cubism has a Spanish origin and that I invented Cubism. We must look for the Spanish influence in Cézanne. Things themselves necessitate it, the influence of El Greco, a Venetian painter, on him. But his structure is Cubist.” – Pablo Picasso

Saint Francis kneeling in Meditation / El Greco (Domenico Theotocopuli) / Photo © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images

Find Out More

See El Greco in New York at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 4, 2014–February 1, 2015

See all images by El Greco in the archive

Read more about El Greco and other influential Spanish artist in National Hispanic Heritage Month: The 10 most influential Hispanic artists through history.

All images in this article are sourced from bridgemanimages.com. Contact the Bridgeman sales team at nysales@bridgemanimages.com for more information regarding licensing, reproduction and copyright.