Berthe Morisot: Portrait of an Artist

Life and work of one of the lesser known Impressionists, Berthe Morisot (1841-95).

Manet’s Muse

You may not know her name, but it is likely you know her face. Morisot was the model and muse to Edouard Manet, appearing in some of his best known works, including ‘The Balcony’. But Morisot was far more than a model, having established herself as a distinctive and dedicated artist. Her relationship with Manet was a mutually beneficial one, each providing inspiration for the other’s work. Unlike Manet, however, Morisot firmly identified herself with the Impressionist movement, exhibiting with them from the very first show at Nadar’s studio on the Boulevard des Capucines in 1874.

She painted what she knew; comfortable domestic scenes, with hints towards the restrictive nature of life as a bourgeois wife and mother. How she paints her life is in marked contrast to how Manet portrays her. For him she is a symbol of the ‘modern woman’, independent and free-spirited, with a touch of the femme-fatale. This blog will, briefly, explore these two aspects of Morisot’s life, painting a picture of what it was to be a woman in late 19th century Paris.

Born to an haute bourgeois family in 1841, Morisot and her sister received the style of art education common to girls of their class. She registered as a copyist at the Louvre, where she met the influential Barbizon painter Camille Corot. It was Corot who inspired Morisot to begin painting ‘en plein air’ (outdoors), a method now synonymous with the Impressionist movement. She met Manet in 1868, and drew him into the circle of painters who would become known as the Impressionists. It was she who persuaded Manet to paint ‘en plein air’, a considerable departure from his usual style. Manet’s portraits of Morisot from this period demonstrate a striking immediacy. His most famous image of her, ‘Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets’ (1872) is a modern, spontaneous vision of fashionable beauty; a face glimpsed on the streets of contemporary Paris and committed to canvas.

Manet seemed to use Morisot as the model of modern femininity, often posing her with fashionable accessories such as fans, veils and slippers.

Two Sisters: Life and Work

Morisot’s own paintings owe no small debt to the language of fashion. Take arguably her most famous work, ‘The Cradle’, everything in the painting demonstrates the best in contemporary taste, from the mother’s clothing to the beautifully draped crib. It is often seen as an image of domestic bliss, with a calm, serene atmosphere. However, the abundance of white drapery and the wistful gaze of the mother lend a rather melancholy and claustrophobic air to the painting.

The same feeling pervades many of Morisot’s portraits of her family, particularly those of her sister, Edma. Edma was a keen painter herself, having received the same art education as Morisot, and the sisters shared a studio. However, unlike Morisot, Edma abandoned painting when she married, something she laments in her correspondence with her sister:

“…I am often with you in thought, dear Berthe. I’m in your studio and I like to slip away, if only for a quarter of an hour, to breathe that atmosphere that we shared for many years…”

Looking at ‘Portrait of the Artist’s Mother and Sister’, painted around the time of Edma’s marriage, one can sense the air of restrictive comfort. Edma in particular seems lost in thought, perhaps thinking of the wider world outside her domestic bubble, hinted at by the glimpse of an open window reflected in the mirror above her head.

Portrait of the Artist’s Mother and Sister, 1869-70 by Berthe Morisot / National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Later life and legacy

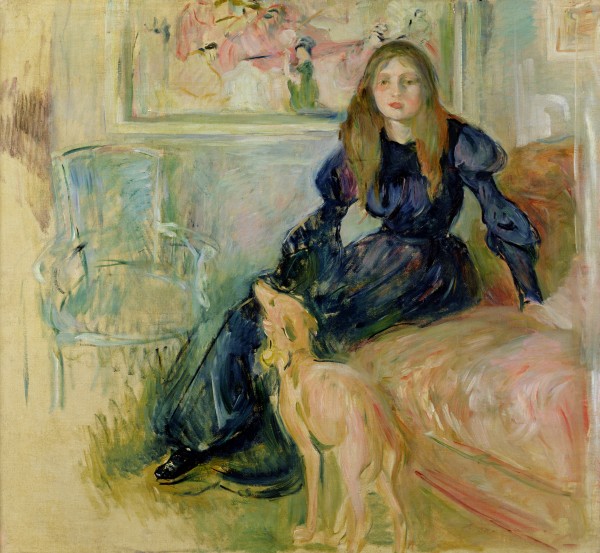

In contrast to her sister, Morisot’s own career continued to flourish after her marriage to Manet’s brother Eugene in 1874. She had already won the patronage of Paul Durand-Ruel (the subject of the National Gallery’s exhibition) and in 1875 achieved the two highest prices at the Hotel Drouot auction. She developed a looser style in her later career, seen in the portraits of her daughter, Julie These are joyful, vibrant works, which reveal a happy and creative life.

It seems Morisot embodied all the contradictions of what it was to be a woman in late 19th century Paris; free-spirited and dedicated to her craft but also very aware of her place in society, and the strictures of that life. It is telling that when she died on March 2nd 1895, her obituary neglects to mention anything about her painting; she is a wife and mother and nothing more. Thankfully, 120 years on, her talent is celebrated as it should be.

Find out More

Get in touch with the Bridgeman team on uksales@bridgemanimages.com with enquiries about licensing images and clearing copyright