Claude Monet, Beyond the Water Lilies

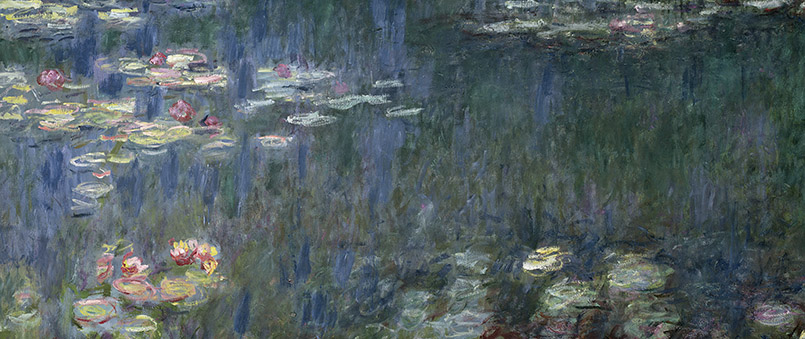

Probably Monet’s most recognizable work, the Water Lilies series, is without doubt a masterpiece and a trademark of the Impressionism movement. Monet painted this series in his garden at Giverny between 1900 and 1926, near the end of his life, but before the Water Lilies there is so much more that makes Monet ‘the ultimate Impressionist’.

To celebrate the 175th anniversary of the artist’s birth (November 14, 1840), we honour him by presenting some of his best loved works before the water lily paintings.

Wild Poppies, near Argenteuil, 1873 by Claude Monet (1840-1926) Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France / Bridgeman Images

Monet painted Wild Poppies (Les Coquelicots) in 1873 in Argenteuil, a small village where he settled for a while and where he painted some of his best-known works. The vibrant colours and flowing rhythm are characteristic of Monet’s work and so is the way the boundaries between the human figure and the surroundings melt.

Towards the end of 1873 a group of artists (among them Monet) were constantly rejected by the conservative Académie des Beaux-Arts. They called themselves Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors and Engravers, and soon they would be known as The Impressionists.

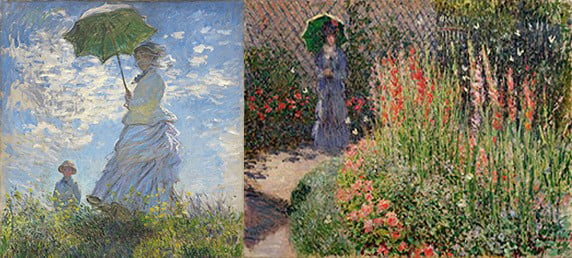

Monet’s Woman with a Parasol (1875) and Gladioli (c1876), are fine examples of the Impressionist style with visible brushstrokes. At the time, however, the art movement was severely criticized by the juries from The Paris Salon, accusing the Impressionists of doing art carelessly, “the way they whitewash granite for a fountain.” [1]

Woman with a Parasol, 1875 National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, USA; Gladioli, c.1876

Detroit Institute of Arts, USA / City of Detroit Purchase

Although the subject in Monet’s painting was mainly his garden, nature and the countryside, on occasions he painted the city. The Rue Montorgueil and Rue Saint-Denis (Celebration of June 30, 1878) are two examples of these unusual yet powerful portraits of the busy streets of Paris, where details lost by the crowd and it is colour – rather than shapes – what forms the image.

The Rue Montorgueil, Paris, Celebration of June 30, 1878, Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France; The Rue Saint-Denis, Celebration of June 30, 1878, Musee des Beaux-Arts, Rouen, France / Bridgeman Images

In contrast to the Academic artists, Monet did much of his painting outdoors and Chrysanthemums (below) is one of the rare occasions where he painted flowers indoors. It was during the autumn of 1878, possibly the bad weather and the fact that his wife died, is what drove him to paint it. Cut off by his disapproving bourgeois family and overwhelmed by grief and financial worries, Monet devoted his time to paint still-life’s as a source of income, since they sold better than landscapes.

By 1880, Monet’s situation began to improve and in 1904, he went to London where he found new sources of inspiration.

The Houses of Parliament, London, with the sun breaking through the fog, 1904 Musee d’Orsay; The Houses of Parliament, Sunset, 1904

Private Collection / Photo © Christie’s Images

It is known that Monet was interested in experimenting the natural effects of light and colour on surfaces. He often painted several series of the same subject under different atmospheric conditions at different times of the day to study the ephemeral movement of light and to capture its diffuse quality. The effects of mist on the Thames were no exception and immediately captured Monet’s attention. With broad, quick brush strokes he painted the Houses of Parliament series, where we can recognize a progressive dissolution of edges, so characteristic of his work: details dissolving into light and shadow, the stones of the building dissolving into the water, shapes being transformed into relatively formless patches of colour.

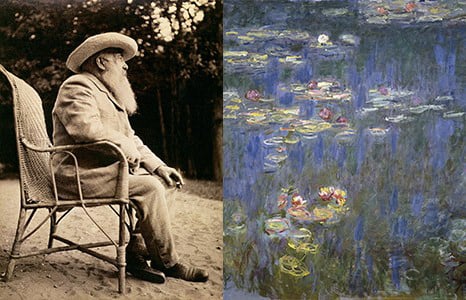

Claude Monet (1840-1926) in the garden of Giverny, 1915 (1840-1926) by French Photographer / Private Collection; Water Lilies, detail, De Agostini Picture Library / A. Dagli Orti

Monet painted the water lilies in the last years of his life. The iridescence of the hues and the splendor of his masterwork reflect the peace Monet probably found in his quiet garden in Giverny and the recognition his work received. As he outlived most of the impressionists, he was able to witness the acceptance of the Impressionism movement.

On the 175th anniversary of his birth we celebrate his ability to express the inexpressible by capturing the very essence by direct – careful – observation of nature.

Sources

[1] Claude Monet, Wings Books, 1992

Find out more

Painting the Garden: Monet to Matisse opens at the Royal Academy of Arts from 30 Jan 2016

Image licensing

View all images by Claude Monet in the Bridgeman archive.

Represented collections include Christie’s Auction House and Musée Monet-Marmottan in Paris.

Contact the Bridgeman team via their offices in New York, London, Paris and Berlin for image licensing enquiries.