No ordinary love: 200 years of Sade

Confined to the mental asylum of Charenton, Sade wrote his last will and testament on 30 January 1806.

Even in his own lifetime he was an infamous figure. In the 1760s and 1770s he had existed in the public imagination as a poisoner, torturer and vivisectionist. Now towards the end of his life Parisians came to visit Charenton’s theatre that was directed by the still sulphurous marquis. In the face of such notoriety, Sade requested a burial that would commit him to oblivion:

“Once the ditch is covered over with earth, it will be strewn with acorns, so that the spot may become green again, and the copse grown back thick over it as it once was. The traces of my grave may disappear from the earth as I trust the memory of me shall fade from the minds of men.”

These wishes were ignored. Sade was given a Christian burial, and although the authorities and his family tried to efface his memory by banning and destroying his works (his son, for instance, tore up the manuscript of his last completed novel), Sade’s fame has continued to grow and grow.

|

|

|

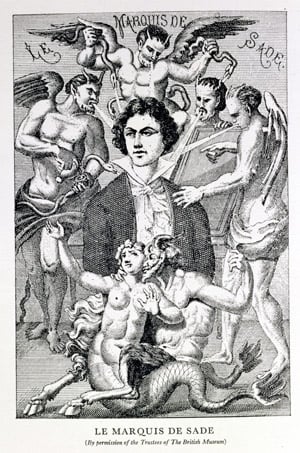

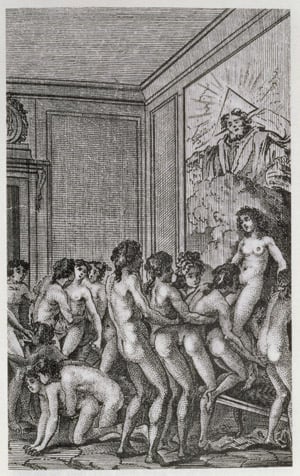

| Portrait of the Marquis de Sade Surrounded by Devils (engraving), French School, (18th century) | Illustration for the first edition of ‘Histoire de Juliette’ by the Marquis de Sade c.1797 (engraving) |

Commemorating the legacy of Marquis de Sade

2 December 2014 is the 200th anniversary of Sade’s death, and a series of high-profile events testify to the unassailable but controversial place he occupies in the cultural landscape. Three events are especially noteworthy. The Musée d’Orsay’s immense (and rather incoherent) exhibition Sade. Attaquer le soleil aims to show how Sade opened up new ways of representing ferocity and desire, and so influenced generations of artists.

Also in Paris, the Musée des manuscrits et lettres is displaying its most precious acquisition: the manuscript of Sade’s most violent, extreme and delirious work, The 120 Days of Sodom. Comprising dozens of bits of paper glued together to form a 12-metre long roll, this astonishing object was pillaged from Sade’s abandoned cell at the Bastille, its loss causing the marquis to shed ‘tears of blood’. Seeing the dense, minuscule writing that obsessively covers every square inch of the paper brings one into Sade’s presence, and the effect is not altogether pleasant.

And opening on 6 December at the Fondation Bodmer in Geneva is another exhibition, Sade, un athée en amour, which promises to ‘discard the prejudices and commonplaces that have accrued to this major author who will be encountered in his most intimate works and writings.’ I’m intrigued that the visitor is promised a personal, intimate meeting with Sade, and I’m not sure that I’d personally welcome such a tête-à-tête with the writer whose works I nonetheless admire greatly.

|

|

|

| Sadistic Orgy, illustration for the first edition of ‘Histoire de Juliette’ by the Marquis de Sade, c.1797 (engraving) | An Orgy, illustration from ‘Histoire de Juliette’ by the Marquis de Sade, 1797 (engraving) |

Sade is now recognised as a major figure of the Enlightenment

He is best known for works like Justine and Philosophy in the Boudoir, in which graphic, unusually complicated and often violent sex goes hand in hand with philosophical discussions. These works make great demands of the reader: the ferocity can unsettle, but the unique intellectual and aesthetic payback is immense, as I hope readers will recognise when my new translation (in collaboration with Dr Will McMorran) of The 120 Days of Sodom appears with Penguin Classics in 2015. Sade is now recognised, especially in France, as major figure of the Enlightenment, and his analyses of power, desire, selfhood, gender and religion take their place alongside those of canonical figures as such Locke, Voltaire and Diderot.

Sade is not a pornographer, he is a thinker

His challenging work has been taken up by such important figures as Simone de Beauvoir, Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault. Over the last few years the image of Sade has changed as the full range of his writings has emerged. The variety of Sade’s writing is considerable, including lively and passionate correspondence (mostly written from behind bars), historical fiction, plays, short stories, and even some travelogues. One of these, the Voyage to Italy, was written when he was on the run following a scandal at the family chateau in Lacoste. It includes information on the countless works of art that Sade admired in Italy, and indeed there is a visual element to much of his work, from the magnificent character portraits to the precisely described tableaux that structure his sex scenes. And of course the erotic works include astonishing illustrations that Sade himself oversaw.

It is no surprise then that Sade has exerted such an influence on visual artists, including Man Ray, Hans Bellmer, Luis Buñuel, Dali and Pier Paolo Pasolini.

The Games of the Doll, Plate II, 1949 (hand-coloured gelatin print) by Hans Bellmer (1902-75) / Mayor Gallery, London / Bridgeman Images

What, finally, is the point of reading Sade?

He is not an author like any other; the canon may have broadened but the violence will always remain a problem for many readers. Sade offers no easy comfort or solace, but he commands to be read and re-read. I’d argue that it is precisely by placing the reader in extreme situations that Sade remains a writer of considerable value. A couple of weeks ago Colin Burrow wrote in the London Review of Books that literature matters ‘principally because it is a provocation to ethical and political thought.’ And I’d suggest that Sade provokes ‘harder, better, faster, stronger’ than any other author out there. In a period of easy assumptions, acquiescence and apathy, he remains vital.

Find out more

All images for this feature are from bridgemanimages.com.

Contact uksales@bridgemanimages.com for more information regarding licensing, reproduction and copyright of images.