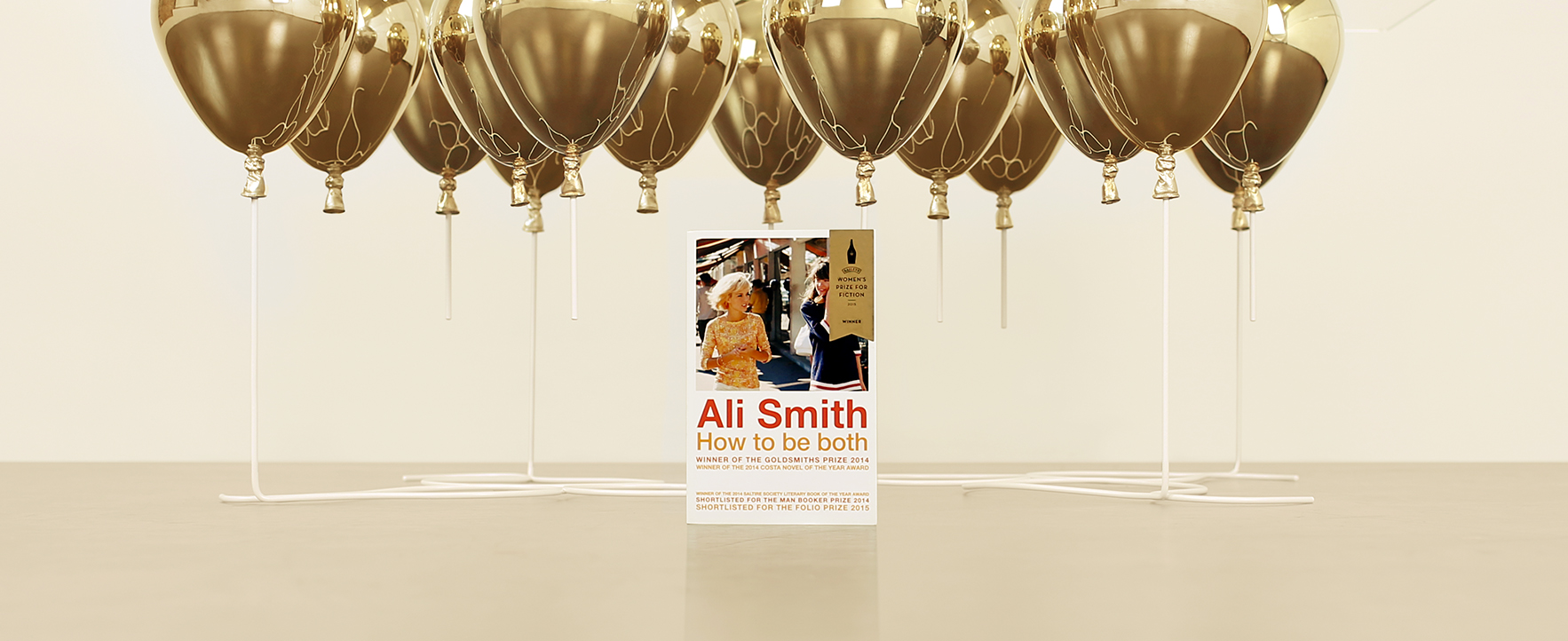

The Artful Duality of Ali Smith’s Novel

In the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction winning novel How To Be Both, the intertwined stories of a 15th-century painter and a 21st-century teenager illuminate questions of art, identity, and immortality.

The expansive nature of Ali Smith’s novel is highlighted by the interesting juxtaposition of the cover photograph of 60’s singers Sylvie Vartan and Francoise Hardy and the Renaissance frescoes used on the inside cover depicting figures from Palazzo Schifanoia. Here’s an exploration of the themes of the novel and the significance of these frescoes.

Thoughts on the Book

The narrative structure is unusual, in that the story can be read in either order, with George, a girl living in present-day Cambridge, or a fictionalised account of the painter Francesco del Cossa, an artist in 15th-century Ferrara. In fact, the book was published in two different versions, half beginning with one story, and half with the other. The story flows in a first person, stream of consciousness style, which is disorientating at first, but creates a sense of intimacy between the reader and the two protagonists; it is as if we are hearing their every thought.

Exploring Frescoes and Francesco

One of the Three Decans who Oversee the Month of March, Il Salone dei Mesi, 1470-99 by Francesco del Cossa. Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara, Italy/ Alinari/ Bridgeman Images

Dean, detail from Sign of Aries, scene from Month of March, Il Salone dei Mesi, 1470-90, (fresco) by Francesco del Cossa (1435/6-c.1477) Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara, Italy/ DeAgostini/ Bridgeman Images

Very little is known of del Cossa’s life, and it is this that allows Smith to weave a deep, but playful, narrative around him. In fact, Smith has it that the artist was born a girl, but takes on a male identity. George, the modern day teenager, first encounters the artist’s work while on holiday with her mother in Ferrara. George’s mother is drawn to a figure she’s seen from the frescoes of the Palazzo Schifanoia, and travels to Italy to see the original.

The figure is from the Sign of Aries fresco and it is not hard to see why George’s mother is so captivated. He is a strange and beguiling figure, standing in his ragged, white clothing, holding the end of a piece of rope that’s tied around his centre. What follows in the book is a wonderful scene of George and her mother discussing the possible meaning behind the myriad of allegorical figures that adorn the palace walls. It’s an art historians dream, and a rare thing to encounter in the pages of a novel.

We also see the frescoes from the point of view of the artist, as the book recounts del Cossa’s experience of painting them. It shows how a work of art can not only speak to us across hundreds of years, but how it can be viewed through the prism of our own experience.

Curiousness of del Cossa

We discover more about del Cossa’s art as the book progresses. George visits the National Gallery in London after her mother’s untimely death. She is there to view the only two paintings by del Cossa in the UK. One is an image of ‘Saint Vincent Ferrer’, the patron saint of builders.

St Vincent Ferrer, 1473-1475 (egg tempera on poplar) by Francesco del Cossa (1435/6-c.1477) National Gallery, London/ DeAgostini/ Bridgeman Images

We don’t know why del Cossa chose this particular saint for the central panel of a Bologna altarpiece, but it is interesting to note that the only fact we have on the artist is that he was the son of a stonemason. Surely this saint must have had particular significance for his family?

Again, Smith’s novel highlights the strangeness of del Cossa’s work. The layers of symbolism and allegory seem entirely alien to the modern viewer. In fact George notes, as she sits for hours in front of it, how few people even notice the painting, let alone spend any time studying it.

This, in some ways, is the difficulty of art galleries. The paintings are entirely removed from their original context, and it’s impossible for visitors to give equal attention to every work on display. No wonder most visitors chose to focus on the more famous works. However, as Smith’s novel shows, there is much to be gained from focusing on the lesser known artists. How their stories can inspire us and even mirror our own experiences, 100s of years after their death.

Find out More

How to Be Both is a 2014 novel by Scottish author Ali Smith, first published by Hamish Hamilton. It was shortlisted for the 2014 Man Booker Prize. and won the 2014 Goldsmiths Prize, the Novel Award in the 2014 Costa Book Awards and the 2015 Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction.

Images for Licensing

The Bridgeman archive is the perfect place to find inspiration. Take some time to search and you could discover your own Francesco del Cossa.

Get in touch with the Bridgeman team on uksales@bridgemanimages.com with enquiries about licensing and clearing copyright.