Umberto Boccioni and Futurism

The 17th August 2016 marks a century since the death of the highly influential Italian painter and sculptor, Umberto Boccioni. He was one of the principle figures of the revolutionary aesthetic of Futurism, an art movement that emerged in Italy in the years before the First World War.

Futurism highlighted technology, speed, youth and violence, as well as the car, the aeroplane and the industrial city. It glorified modernity and hoped to liberate Italy from its past. The artistic and social movement was practised in every medium of art and was paralleled in England, Russia and elsewhere.

In honour of the 100 year anniversary of Boccioni and our increasingly technological age, explore works by the artist and some of his Futurist contemporaries:

Umberto Boccioni (19 Oct 1882 – 17 Aug 1916)

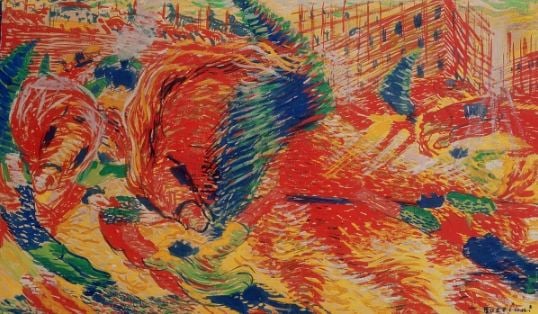

Boccioni not only developed the theories of Futurism, but also introduced visual innovations that led to the dynamic, Cubist-like style that is associated with the movement. His The City Rises is regarded by many to be the very first truly Futurist painting; it captures the group’s fondness for the modern city. The artwork took a year to complete and was exhibited throughout Europe.

The City Rises, 1911 (tempera on card), Umberto Boccioni / Jesi Collection, Milan, Italy

Boccioni emerged first as a Neo-impressionist painter, drawn to landscape and portrait subjects. It was not until he encountered Cubism in around 1911 that he developed a distinct style that lay at the heart of Futurism. He borrowed the typical geometric forms of the French style to evoke dynamism and violent social upheaval. He felt that scientific advances and modernity called for the artists to abandon the custom of depicting static, legible objects; they should represent movement and the experience of flux: he called this ‘physical transcendentalism’.

“In the brief life span of the Italian Futurist movement, the short-lived Umberto Boccioni was a blazing comet… drafting two Futurist manifestoes in 1910 and 1912 that … called for an art that glorified speed, violence and the machine age, one that above all reflected the dynamism of an engine-driven civilization.” – Grace Glueck, New York Times Art Critic

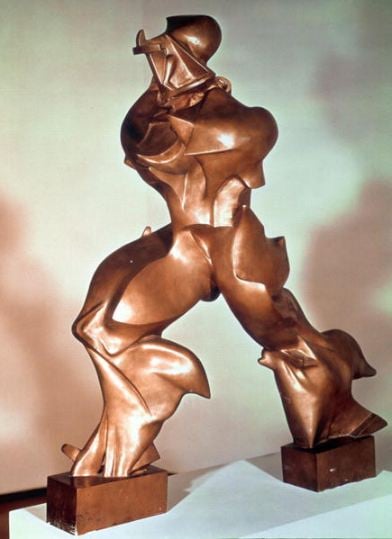

Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913 (bronze), Umberto Boccioni / Mattioli Collection, Milan, Italy

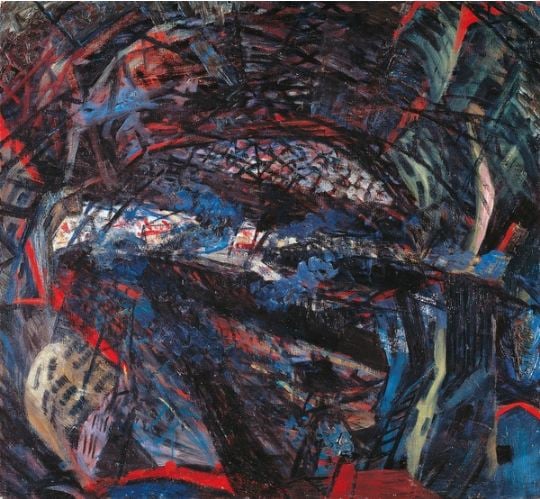

Materia, 1912 (oil on canvas), Umberto Boccioni / Private Collection

Other Significant Italian FuturistsThe artist later progressed from painting to create some significant Futurist sculpture. Sadly, at the premature age of just thirty-three, Boccioni died while volunteering in the Italian army. Despite his short life, his approach to the dynamism of form and the deconstruction of solid mass guided artists long after his death. His death became emblematic of the Futurists’ celebration of the machine and the violent destructive force of modernity.

Giacomo Balla (18 July 1871 – 1 March 1958)

Balla was an art teacher, painter and poet and later participated in Futurism. In his works he was able to create a pictorial depiction of light, movement and speed. The latter is particularly evident with his Dynamism of a Dog on a Lead, which was inspired by chronophotography: movement captured in several frames of print. He also adopted the dynamic expression of velocity in machine forms to explore and convey motion.

Balla was largely self-taught as an artist, excluding some evening classes and two months at the Albertina Academy. His early works were portraits, landscapes and caricatures, partly influenced by the Italian Divisionists, and he later became increasingly fascinated with painting aspects of modern industrialised life. He signed the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting in 1910 and quickly became one of the most original and inventive of the Futurist painters, even going on to teach Severini and Boccioni.

See more: BMW car using Balla image licensed from Bridgeman

Carlo Carra (11 February 1881 – 13 April 1966)

Carra was a leading figure of the Futurist movement and in addition to his numerous paintings, he also wrote several art books and instructed others on art in Milan. Shortly after enrolling at the Brera Academy and studying under Cesare Tallone, he signed the Manifesto of Futurist Painters and started the most influential and popular phase of his artistic career.

Leaving the Theatre, 1910-11 (oil on canvas), Carra, Carlo / Estorick Collection, London, UK

Milan station, 1910-1911, Carlo Carra / Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart, Germany / De Agostini Picture Library

After World War I began, Carra’s work adopted fewer Futurist concepts and began to focus more on stillness and form, rather than the motion and feeling that the Futurists admired.

Despite various shifts in styles, the best known work of his oeuvre is his 1911 Futurist painting The Funeral of the Anarchist Galli – an Italian anarchist who was killed by police in 1904 and caused a violent scuffle between police and fellow anarchists. Carra, who was present at the scene, conveys the tension and chaos that he witnessed: the movement and clashing of the bodies and the black flags flying in the air. Carra himself was an anarchist as a young man but, along with many other Futurists, later held more reactionary political views.

Gino Severini (7 April 1883 – 26 February 1966)

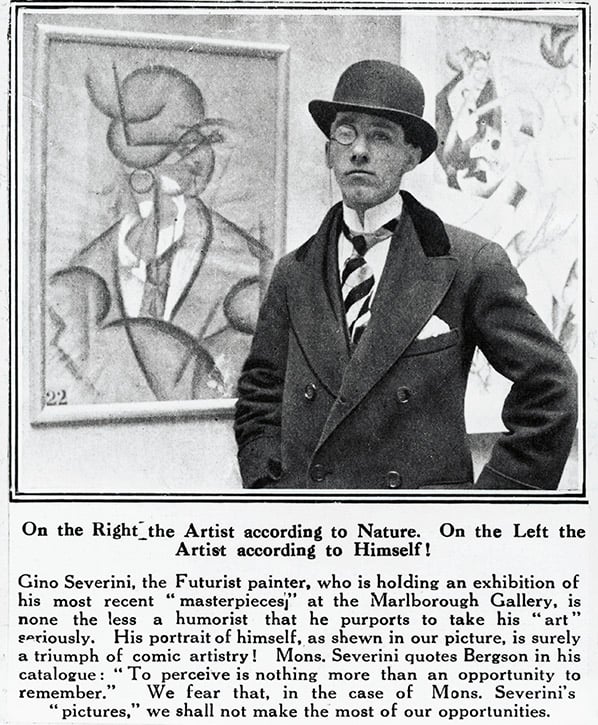

Severini was yet another prominent member of the Futurist movement. He was born into a poor family and gained a keen interest in art when he moved to Rome with his mother; he enrolled in art classes with the help of a patron and attended the free school for nude studies as well. After two years his formal education ended when his patron stopped his allowance and declared: “I absolutely do not understand your lack of order.”

Severini met Boccioni in 1900 and together they visited Balla’s studio, where they were introduced to the technique of Divisionism: a new way of breaking the painted surface and colours. This had a great influence on the artist’s early work and on Futurist painting as a whole between 1910-11.

The Italian painter Gino Severini (Cortona, 1883-Paris, 1966), picture from The Oulokeer, London, April 26, 1913. Italy. / De Agostini Picture Library

Severini was yet another artist invited to co-sign the Futurist manifestos by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Boccioni. Due to his connections with both France and Italy, Severini encountered Cubism before his Futurist colleagues and thus helped to encourage a Cubist-style among the Futurists and a new means of expressing dynamism. The artist helped to organise the first of the movement’s exhibitions outside of Italy, which led to subsequent shows in Europe and the United States.

Unlike his contemporaries, Severini was more interested in the expressive motion of dancers than the subject of machines and was particularly adept at rendering lively urban scenes.