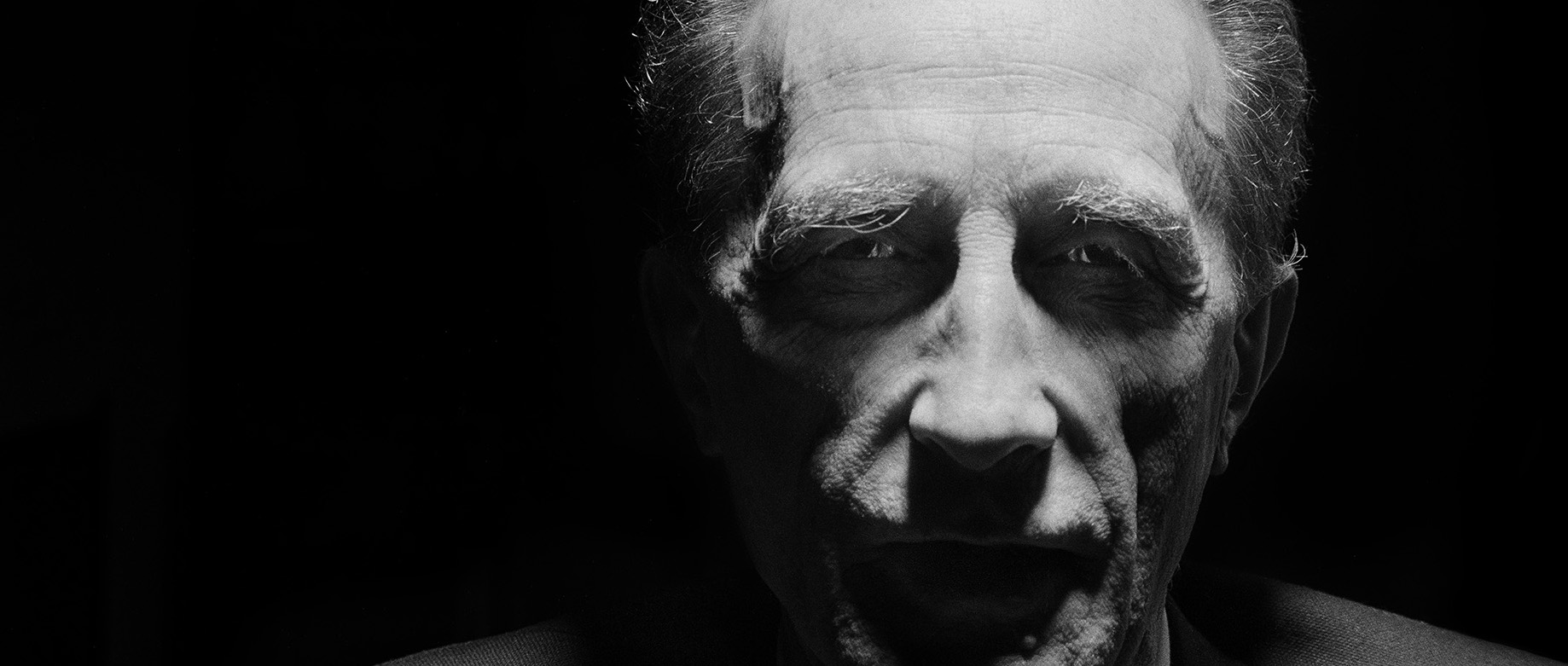

Marcel Duchamp: 50 Years Since His Death

Marcel Duchamp rose to notoriety in the 20th Century, pushing the boundaries of what art could be with his scandalous ‘ready-mades’, sculptures and paintings.

When researching Duchamp, I came across a clip of an interview between the artist and James Johnson Sweeny, former director of the Guggenheim Museum, produced by the National Broadcasting Company in 1956. The documentary opens on a shot of Duchamp himself standing in front of the original The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, examining the web of cracks that distort the texture of the glass panels’ surface. Duchamp is dwarfed by the magnitude of his piece, alternately stooping and craning his neck to examine it under its spotlight in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The scene appears a little staged (when Sweeny enters he is apparently mildly surprised to find Duchamp) but Duchamp’s engagement with his work seems genuine. He is considering the damage done to his famed and constantly in-progress piece, and describes how a journey in the back of a lorry shot cracks through the glass panes. There is a striking calmness in his story telling, a sort of delight in the hazardous adventures of his work. He says aloud to Sweeny, ‘The more I look at it, the more I like it…The two crackings are symmetrically arranged and there is…almost an intention there…a ready-made intention, in other words, that I respect and love.’

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) 1915-23 (oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire & dust on glass panel), Marcel Duchamp, Marcel (1887-1968) / Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, PA, USA / Bridgeman Images

This respect for the development of a piece, whether strictly intentional or not, is essential to Duchamp’s approach to art. While he keenly asserts in an interview conducted after the 1966 Tate retrospective of his work, that the progression of his style (whether surrealist paintings or sourced ‘ready-mades’) was wholly organic, Duchamp suggests his life as a whole was art in itself. He talks of:

“using painting, using art, to establish a modus vivendi, a way of understanding life, that is to say, to try and make of my life itself a work of art, instead of spending my life making works of art in the form of paintings or sculptures.”

He continues,

“one can very well make of one’s life- the way one breathes, behaves, reacts to things or to people- one can easily understand it as a painting, if you will, a tableau vivant, even a cinematic picture.”

There is something so attractive about the concept of one’s very life being an artistic statement, but something a little uncomfortable about it too, hence the scandal that originally surrounded Duchamp’s work. It is through the lens of this attitude that Duchamp’s infamous ‘ready-mades’ appear a natural progression. When one lives a work of art, “The choice of the artist is enough”.

Although Duchamp was not directly involved with modern art movements of his time (like Dadaism), he remains a figurehead for artistic explorations of the avant-garde. He lived it, and embodies it still. Nicolas Calas, art critic and poet during Duchamp’s career, agreed with his approach, saying:

“I don’t see Duchamp as having broken the painting, for me it’s the person that counts. It’s more important to be oneself than anything else, and the painting is an activity of the being.’ Duchamp himself categorised paintings as being ‘retinal art’, and conceptual art as ‘in the service of the mind.”

He expanded the capabilities of a piece, and so was loathe to return to the restraints of the traditional painting.

In the words of Bill Copley, Surrealist artist, Duchamp realised that “painting is something above the canvas”, he reached a point “where art left the canvas to become life.”

Today, fifty years since Duchamp’s death, his work still stretches a contemporary understanding of art. As long as echoes of ‘But I could do that!’ continue to haunt modern art exhibitions, Duchamp’s work will continue to fascinate.

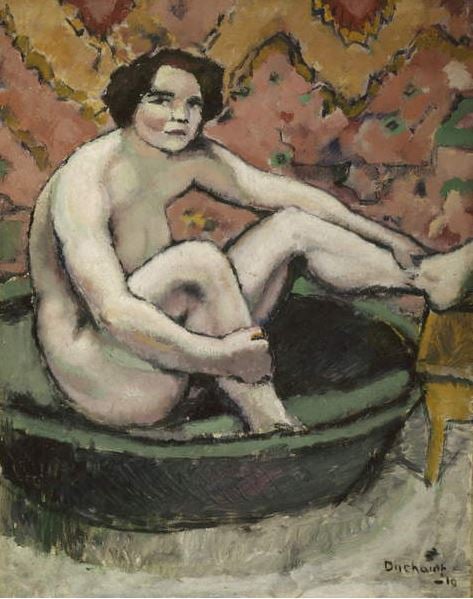

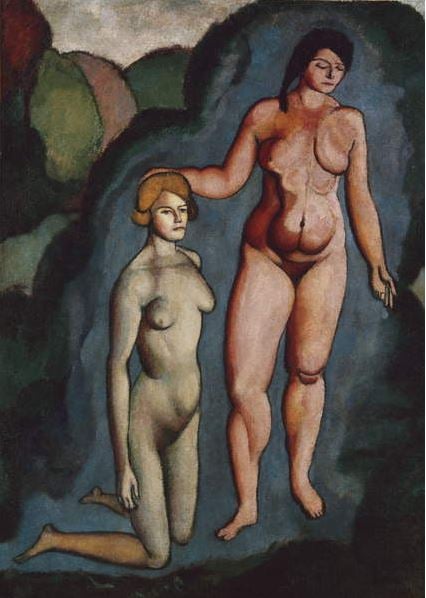

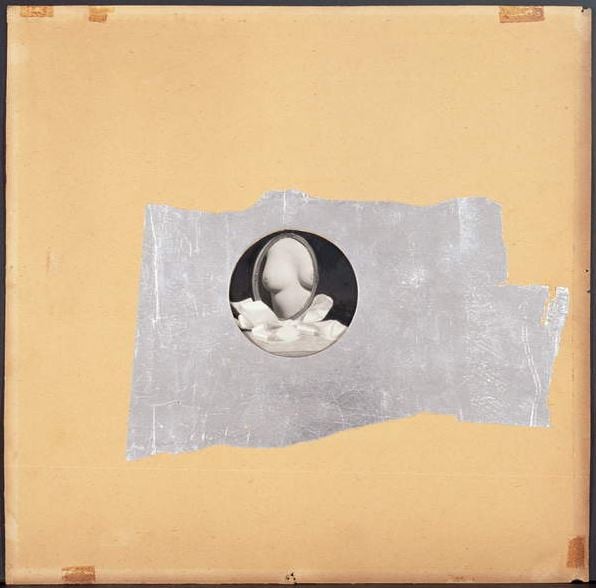

Below is a small selection of Duchamp’s most famous works. His range of mediums, and skill in each is extraordinary.

Nude Seated in a Bathtub, 1910 (oil on canvas), Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) / The Art Institute of Chicago, IL, USA / Gift of Mrs. Marcel Duchamp / Bridgeman Images

The Bush, 1910-11 (oil on canvas), Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) / Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, PA, USA / The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950 / Bridgeman Images

Nude Descending a Staircase, No.3, 1916 (graphite, pen & ink, paint, crayon and wash on paper), Duchamp, Marcel (1887-1968) / Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, PA, USA / The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950 / Bridgeman Images

In the manner of Delvaux, 1942 (collage on cardboard), Duchamp, Marcel (1887-1968) / The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel / Vera & Arturo Schwarz Collection of Dada and Surrealist Art / Bridgeman Images

Fountain, 1917/64 (ceramic), Duchamp, Marcel (1887-1968) / The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel / Vera & Arturo Schwarz Collection of Dada and Surrealist Art / Bridgeman Images

Wedge of Chastity (Coin de Chastete) 1954/63 (bronze & dental plastic), Duchamp, Marcel (1887-1968) / The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel / Vera & Arturo Schwarz Collection of Dada and Surrealist Art / Bridgeman Images

Find out more:

See more of Marcel Duchamp‘s work