Charles Rennie Mackintosh: Father of the Glasgow Style turns 150 years old

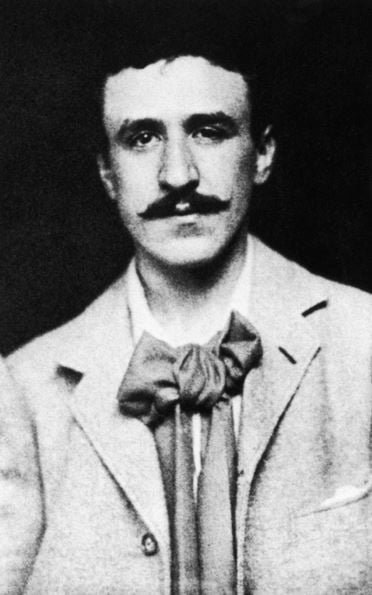

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (7 June 1868 – 10 December 1928), architect, designer, fine artist and the founder of the “Glasgow Style” or the “Glasgow School” turns 150 in June. We take a brief look at the great man’s career and work.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928). Scottish architect, designer and painter. Photograph, c.1900.

The beginning..

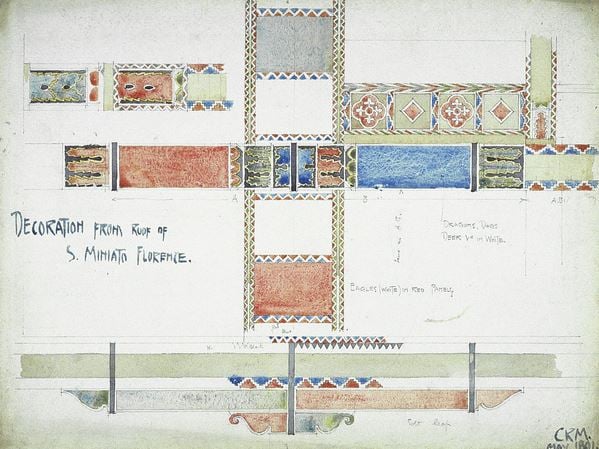

Born in Glasgow on 7 June 1868 (the fourth of eleven children), Mackintosh was apprenticed to a local architect John Hutchison, but in 1889 he transferred to the larger, more established city practice of Honeyman and Keppie. He attended various drawing classes in the evening at the Glasgow School of Art to compliment his architectural practice, and it is there that his talent really flourished. He had access to the School’s library where he was able to consult the latest architecture and design journals which meant he became increasingly aware of his contemporaries both at home and abroad. He won a number of student prizes and competitions, including an architectural tour of Italy in 1890 where he made a great number of detailed drawings.

Once back in Glasgow in the early 1890s, he style started to gain maturity. He took on bigger projects at Honeyman and Keppie, including the Glasgow Herald Building (1894) and Martyr’s Public School (1895).

Decoration from Roof of S. Miniato, Florence, 1891 (pencil and watercolor on paper), Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928

The Four and the Glasgow School, mid 1890s

The group known as ‘The Four’ comprised Charles Rennie Mackintosh, James Herbert MacNair (1868 – 1955), and the sisters, Margaret Macdonald (1864 – 1933) and Frances Macdonald (1873 – 1921).

The artists met as young students at Glasgow School of Art in the mid 1890s. Mackintosh and MacNair were close friends and fellow apprentice architects in the Glasgow practice of Honeyman and Keppie, and the sisters were day students at Glasgow School of Art. They formed an informal creative alliance which produced innovative and at times controversial graphics and decorative art designs which made an important contribution to the development and recognition of a distinctive Glasgow Style. It is at this time that Mackintosh began to promote his idea that the architect should design all things in the building, not just the building itself – a revolutionary idea at the time.

The Glasgow School was born out of The Four, and was largely made up of influential artists and designers living in Glasgow at the time.

Margaret Macdonald was to become his wife in 1900 and frequent collaborator throughout his career. Theirs was a great love story, and Mackintosh credits his wife with being “the genius” in their relationship. In one letter to her he wrote: “You must remember that in all of my architectural efforts you have been the half if not three quarters of them.”

The Heart of the Rose, 1902 (painted gesso over hessian), Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh (1865-1933) / Private Collection

The Glasgow School of Art, 1896

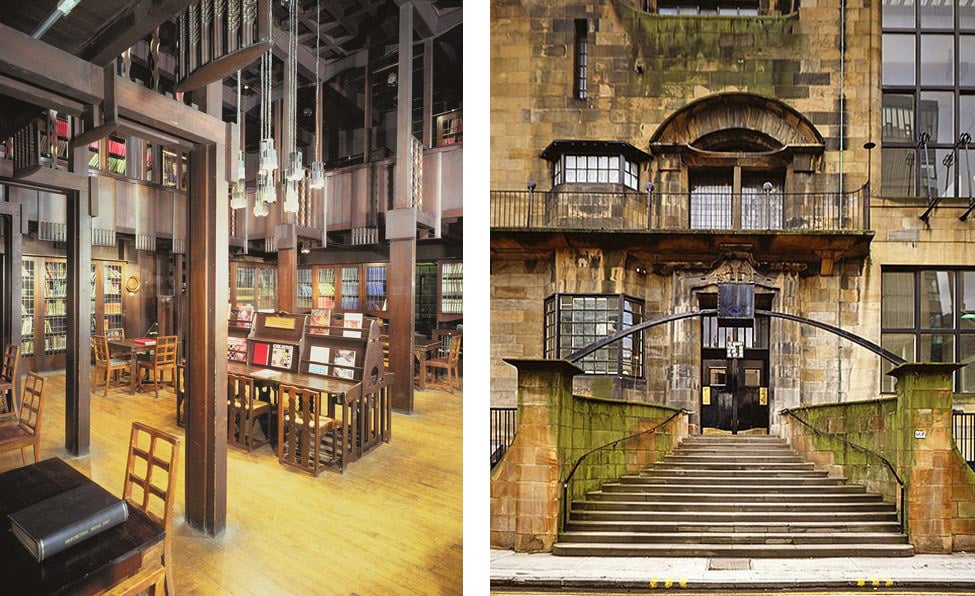

In 1896 Charles Rennie Mackintosh got his biggest commission yet, to design a new building for the Glasgow School of Art was became his Masterwork. Due to lack of funds, the building was carried out in two phases, 1897-99 and 1907-09. This delay allowed Mackintosh to further develop his design and integrate it fully in to the fabric of the building. The exterior took a lot of inspiration from the Scottish baronial style, but use of cutting edge materials and technology gave it a modern twist. The most striking interior he designed was that of the library (which was tragically destroyed in a fire in May 2014), with its creative use of timber beams and columns – a motif greatly influenced by the Japanese aesthetic. The building was in fact a manifestation of all the influences he had absorbed through his reading and travels, and together made a unique style which was to make him internationally famous.

Left: Glasgow School of Art library interior / Photo © Mark Fiennes. Right: Glasgow School of Art, Renfrew Street (North) entrance / Photo © Mark Fiennes

The Hill House in Hellensburg (1904)

The publisher Walter Blackie commissioned Mackintosh to design a large family home which became known as Hill House. His design was influenced by an earlier design he had completed for a competition in Germany called “A House for an Art Lover“, and another domestic building he had designed in 1900 called Windyhill. Its exterior was simple and solid, while its spacious interiors were filled with light, colour, and carefully conceived decoration.

Catherine Cranston’s Tearooms 1896-1917

Glasgow business woman Catherine Cranston was Mackintosh’s greatest patron, commissioning him to design the interiors of a series of tea rooms she was opening throughout Glasgow. He was asked to design the interiors from top to toe – the furniture, lightfittings, wall decoration and even the cutlery. This gave him the freedom to express himself fully.

Left: Portion of Mural for Cranston Tearooms, Buchanan Street, Glasgow, 1896 (photo), Charles Rennie Mackintosh, (1868-1928) & Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh, (1864-1933). Centre: Four spoons for Miss Cranston’s Tearooms, Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) / Private Collection / Photo © Christie’s Images. Right: Side chair, one of a pair, made for Miss Cranston’s Argyle Street Tearooms, Glasgow, 1896 (oak), Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) / Private Collection / Photo © The Fine Art Society, London, UK

The Scotland Street School and moving to London

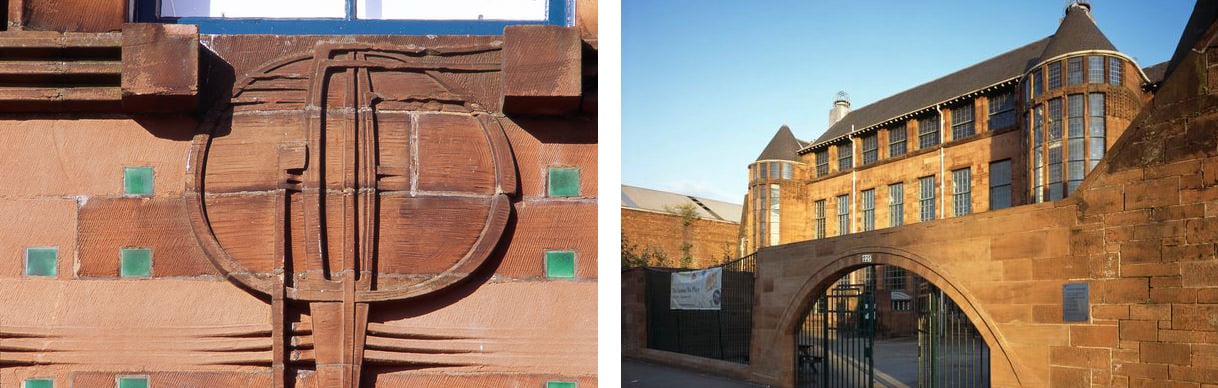

Although Mackintosh had a loyal group of patrons (including Cranston and Blackie) in the UK and was well respected in Europe, he was not widely admired in the UK and struggled to find work. His need to have full control of a building, including the fixtures and fittings, meant that his client base was limited. By 1914, Mackintosh had despaired so much with what he saw as a non-progressive attitude to architecture he decided to move from Scotland. His design for Scotland Street School (1906) in Glasgow was to be his last public commission. He left Glasgow 1916 with his wife, and they moved to London hoping that it would help resurrect his career. While there he worked on a mid-terraced house at 78 Derngate in Northampton. Ultimately the move did not have the effect he had hoped as the First World War had severely restricted building plans in London.

Left: Detail of Ardornment on the south facing elevation of Scotland Street school designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh (photo) / Photo © Iain Graham. Right: View of Scotland Street School from arched the entrance wall which extends up at right angles in a dramatic early modernist vernacular (photo) / Photo © Iain Graham

South of France, 1923 – 1928

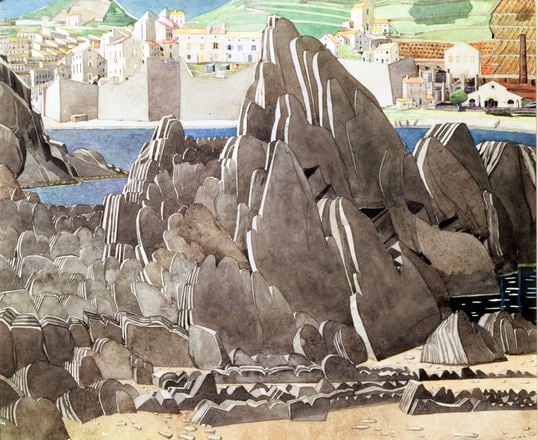

Mackintosh and Margaret moved to the South of France in 1923 where he ceased to produce any more design work. He concentrated instead on his watercolour painting. He was interested in the relationships between man-made and naturally occurring landscapes, and created a large portfolio of architecture and landscape watercolour paintings. Many of his paintings depict Port Vendres, a small port near the Spanish border, and the landscapes of Roussillon.

The Rocks, 1927 (pencil & w/c on paper), Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) / Private Collection / Photo © The Fine Art Society, London, UK

Due to illness he was forced to move back to London where he died on 10th December 1928.

Legacy…

Charles Rennie Mackintosh was never fully appreciated while he was alive, but now he is one of the most revered architects and designers in the world.

Read more posts on architecture:

Masterpieces of Architecture: Kaldor

Life by Design: the Bauhaus and modern living