A Case for the Study of Art History

You will have heard that the Art History A-level was at risk of being axed in the UK –

AQA had dropped the baton, and unless Pearson, the company which owns the examination board Edexcel, rescued it from the floor, the open door for those from unprivileged backgrounds to make sense of a world bombarded with visual media was going to be snapped shut.

My year group were privileged enough to be given the chance to study the subject. As sixteen year olds, like the majority of teenagers, we were pretty image conscious. But Art History A-Level showed us the cogs behind our obsessions.

It enabled us to deconstruct the advertisements which dominated the fashion magazines we poured over. Photo-shopped bodies, like those in Tom Ford’s nude woman-ironing ad from 2008, suddenly became hilarious, something to laugh at, rather than to optimistically emulate.

Nowadays teenagers are exposed to images and video, not just from looking at billboards, magazines, or webpages, but through their social media accounts. Visual culture now sits in the palms of their hands—it’s carried in their pocket.

Young Women Watching A Mobile Phone on Plaza Grande, Quito, Pichincha, Ecuador (photo) / Peter Langer / Design Pics / UIG / Bridgeman Images

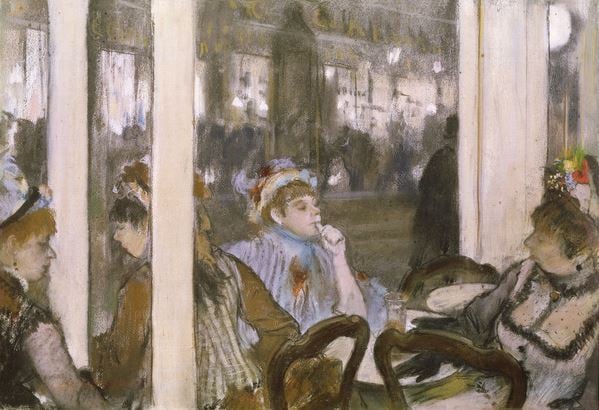

Art history A-level filled in the gaping holes our history curriculum could only gaze guiltily at. And so, as well as having an expert knowledge of Victorian Britain, we learnt about Haussmann’s renovation of Paris though the Impressionists’ grimy café windows.

Women on a Cafe Terrace, 1877 (pastel on monotype), Edgar Degas (1834-1917) / Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France / Bridgeman Images

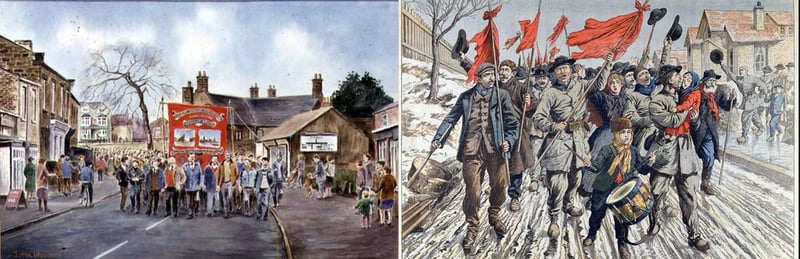

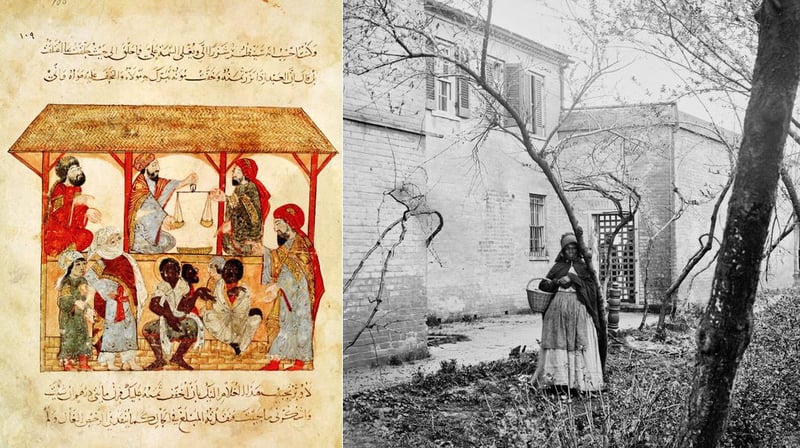

Rather than only study one period at a time, Art History allows you to time-hop—compare works of art from completely different eras and places. 1906 France with 1985 England. 11th century Iraq with 19th century America.

Left: Woolley Miners’ Return, 5th March 1985 (colour litho), John Wood (20th century) / National Coal Mining Museum for England, Wakefield, UK / Bridgeman Images. Right: The Strike of miners in Pas-de-Calais, the procession of the strikers in the mining village, from ‘Le Petit Journal’, 1st April 1906 (colour engraving), French School, (20th century) / Private Collection / Archives Charmet / Bridgeman Images

Left: Ms. Ar 5847 f.105, A Slave Market, from ‘Al Maqamat’ (The Meetings) by Al-Hariri (gouache on paper), Al-Wasiti, Yahya ibn Mahmud (13th Century) / Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, France / Bridgeman Images. Right: Exterior of the slave pen of Price, Birch & Co., dealers in slaves, of Alexandria, Virginia with an African American women standing in foreground. Slave pens, were prisons, to hold slaves awaiting sale. c. 1863 / Photo © Everett Collection / Bridgeman Images

Historical and contemporary visual culture can often act as a sobering mirror. Through it we are given opportunities to learn from other eras and understand that the struggles we are going through now are struggles millions have waded through before.

Teenagers have the right to use visual objects to time travel through different points of history. History is not linear, and art provides flashbacks which then can so pertinently inform our present. Teenagers have the right to be able to analyse, unpick and resist the daily visual onslaught which has slowly become the norm. No other subject curriculum offers this at A-level. This should not only be the privilege of those who attend a private school which offers the Pre-U or the IB.

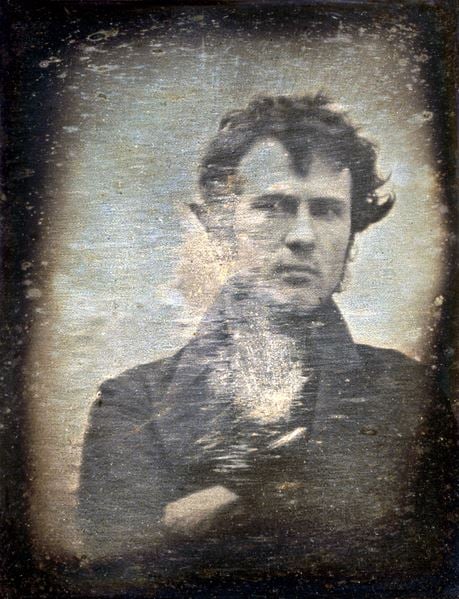

We need to offer every teenager the knowledge that the selfie goes back to Robert Cornelius in 1839; that there is a difference between nude and naked—something John Berger’s Ways of Seeing blew my mind with when I was 17, and that much of the UK’s grandiose city architecture is built from colonial spoils.

Robert Cornelius (1809-1893). Self-portrait daguerreotype by Robert Cornelius, 1839. / Photo © Granger / Bridgeman Images

Thankfully, a multitude of people picked up the baton and Art History A-level was saved at the last minute, after a high-profile campaign.

Music, visual art and film are combining together, in a multitude of forms, sights and sounds. Let’s encourage our young to critically explore this exciting moment, captured so brilliantly at the Hayward Gallery’s Infinite Mix. Let young people debate, analyse, mold and inspire opinions about this in and beyond the classroom. Don’t let it rest blandly on Instagram. Let everyone know you take culture seriously. Let Art History in schools continue, forever and always.

Written by Emily Medd from the charity Art History in Schools, set up to provide solutions to the problems AQA cite as reasons to drop the subject.