5 little-known facts about Magna Carta

June 2015 marked the 800th year anniversary since King John of England put his seal to the ‘Great Charter’, known by its Latin name Magna Carta.

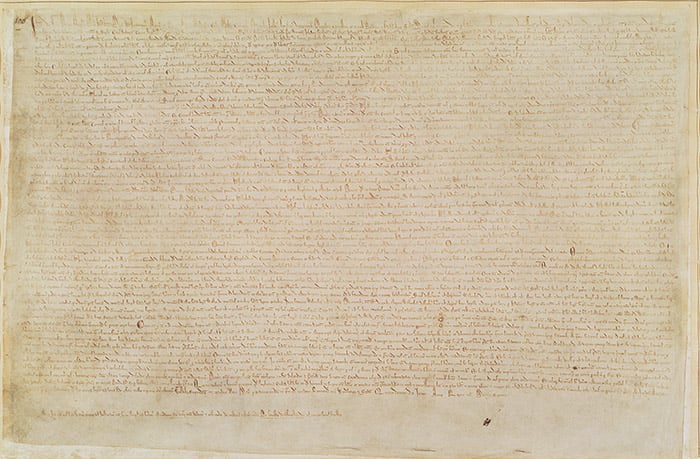

Cotton Augustus II 106 Magna Carta, 1215 (vellum) by English School, (13th century) © British Library Board. All Rights Reserved

This medieval manuscript was first drafted as a peace treaty between the King and a group of rebel barons but at the end became one of the most important legal documents in history. Here are some interesting and less known facts gathered about the Magna Carta:

Failure at its initial form

Created with the intention to bring peace between King John and his barons, Magna Carta failed spectacularly at averting the on-going war at the time between the Crown and the nobles. It was only in 1225, when King John’s son Henry III decided to reissue the Magna Carta at his own coronation in exchange for a grant of new taxes.

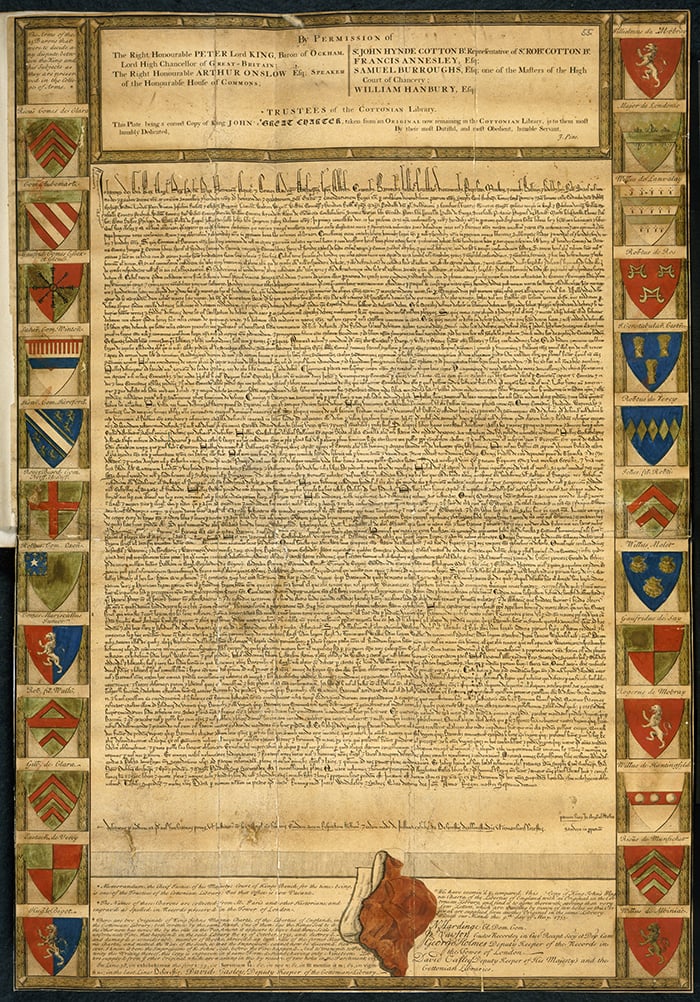

Coloured facsimile copy of the Magna Carta, now catalogued as Cotton Charter XIII.31a, published following the Ashburnham fire of 1731, framed with shields bearing the arms of the barons, and authenticated by the trustees, etc. of the Cottonian Library. / British Library, London, UK / © British Library Board. All Rights Reserved

Its impact today

‘Here is a law which is above the King and which even he must not break. This reaffirmation of a supreme law and its expression in a general charter is the great work of Magna Carta; and this alone justifies the respect in which men have held it’ – Sir Winston Churchill

The original document had 63 clauses, then Henry III reduced it to 27. Today only three of them remain in the books, as the rest are considered too particular to the Middle Ages. However, its legacy had a much stronger influence on the entire English legal system.

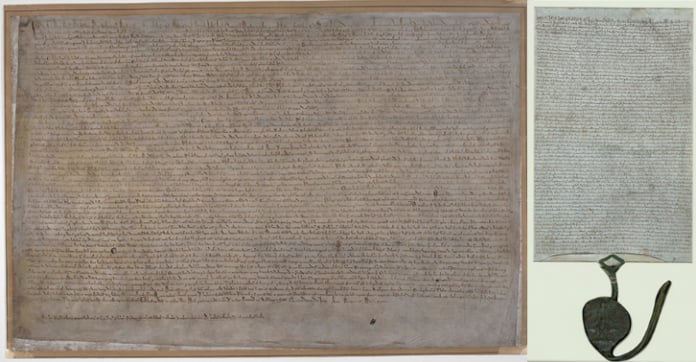

Left – The barons submitting their demands to Henry/ Illustration from ‘Cassell’s Illustrated History of England’

Right – Magna Carta, the final version issued in 1225 by Henry III (vellum), English School, (13th century) / National Archives, UK

Its worldwide importance

“The democratic aspiration is no mere recent phase in human history . . . It was written in Magna Carta.” – Franklin Delano Roosevelt

The core principles of Magna Carta are echoed in the United States Bill of Rights (1791), as well as in many other constitutional documents in the English-speaking world and France.

The Vulture of the Constitution, published by Hannah Humphrey in 1789 (etching), Gillray, James (1757-1815) / Courtesy of the Warden and Scholars of New College, Oxford

Protection of speech

If King John had not sealed the Magna Carta, freedom of speech might not have been possible today. Although it never guaranteed it, the Charter laid the foundation for civil and journalistic rights.

Left: King John (aquatint), English School, (19th century) / Private Collection / © Look and Learn

Right: Great Seal of King John / British Library, London, UK / © British Library Board. All Rights Reserved

No ‘single’ original copy

After its first signing, multiple copies of the original document were prepared and distributed to individual county courts. However, only four still remain today with two held at the British Library, and the rest at Salisbury Cathedral and Lincoln Cathedral.

Left: The Magna Carta. The Great Charter of English liberties, first issued by King John at Runnymede on 15 June 1215. This document is one of the four surviving exemplifications © British Library Board.

Right: Lacock Abbey Magna Carta / British Library, London, UK / © British Library Board. All Rights Reserved

Find out more

Commemorate the 800th Anniversary of Magna Carta with the multiple events happening in 2015

View our archival calendar of historical anniversaries linking through to images and clips up to 2017

For information about researching or licensing clips and images, please contact us

Save

Save

Save