The Works of José Clemente Orozco

José Clemente Orozco (1883-1949) was a Social Realist painter who helped revive the Mexican Muralism movement in the 1920s. His work often depicted human suffering, and his murals are known for being complex, tragic and political.

We had a look at some of his life’s work from his well-known murals to his lesser-known oil paintings and lithographs.

Murals

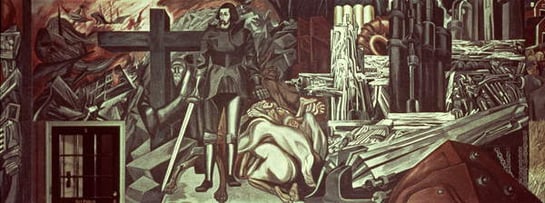

After the overthrow of President Díaz in 1911 and subsequent outbreak of the Mexican Revolution, the new government employed artists in an attempt to redefine Mexican identity and celebrate their revolutionary spirit. Orozco became well-known with muralists Diego Riviera and David Alfaro Siqueiros as “Los Tres Grandes” (The Great Three) for creating beautiful and political art.

In the mural above, Orozco depicts the Battle of Puebla where outnumbered Mexican troops defeated the French on 5th May 1962, a date now celebrated with the Cinco de Mayo holiday.

Although still a dedicated revolutionary, Orozco differed from his peers in that he often depicted the darker side of the revolution. In Katharsis (1934), he depicts the violence, prostitution, and death brought about by war and technology.

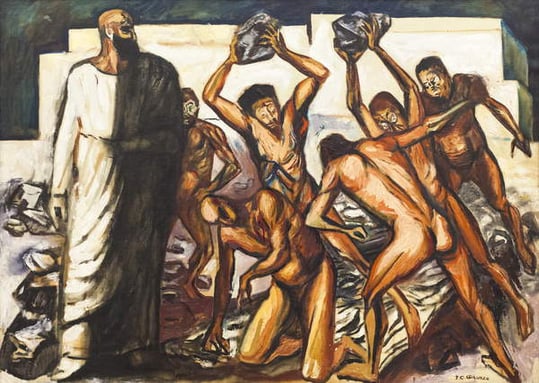

After the Revolution, Orozco travelled to America to continue his political work. Between 1932 and 1934, he painted the Epic of American Civilisation, which consists of 26 panels depicting early Native American migration and subsequent European colonialism. He received international attention from it, and the mural remains one of his best-known works today. In the panel above he depicts Hernán Cortés, the Spanish Conquistador who led the 1518 expedition that led to the fall of the Aztec Empire. This event widely considered the first phase of Spanish colonisation of the Americas, and is portrayed here as a brutal subjugation of the indigenous population.

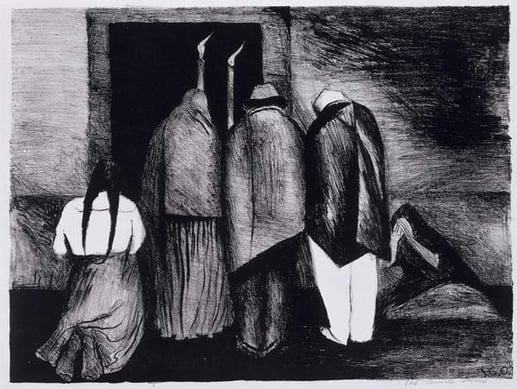

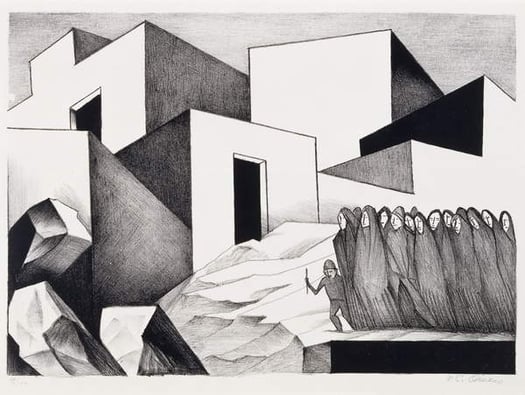

Lithographs

During the Revolution, not everyone had access to murals on government buildings in the city, so “Los Tres Grandes” also made lithograph prints which could be produced in mass and posted both around cities and in the countryside.

However, not all of Orozco’s prints were intended for Mexican revolutionaries, as he was interested in selling his art to an American audience. For this reason, he often decided against depicting violence and horror of the revolution, instead focusing on the resulting loss and sadness. Requiem (1928) depicts mourners at a candle-lit mass, with the ambiguous identities of the figures creating a sense of universality and timelessness.

Orozco saw architecture as a powerful image of human narratives and history. While his murals use the walls of buildings to acknowledge this, many of his prints depict buildings to utilise this imagery.

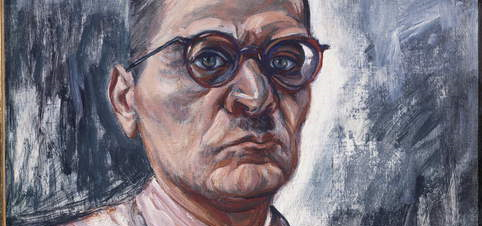

Oil Paintings

Many of Orozco’s early oil paintings were also intended for an American audience, as he sought to challenge U.S. stereotypes of Mexican art.

Despite his appreciation for modern New York architecture, many of his paintings instead focused on the human side of the sprawling urban city. In The Unemployment (c.1928-1930), completed after the Wall Street Crash, he depicts three ambiguous figures against a dark grey wall, a commentary on unemployment as a result of capitalism.

From 1940-1944, although he was still a highly sought-after muralist, Orozco turned more to oil painting in order to revisit themes from his murals. Like in much of his life’s work, he used Christian figures and myths to reflect on contemporary politics, as he was interested in the dynamic and repeating nature of history.