The portrayal of artistic creation in film

‘The muse is born in pain, thrives on it and loves to inflict it’, said Floridian artist Warren Criswell, remarking on the tethering of artistic brilliance to troubled personal lives. With the imminent arrival of two biopics about great artists (‘Rodin‘ and ‘Cezanne and I’), here is a brief examination of how Hollywood has previously depicted the muse of creation, whether by examining the tumultuous lives of the artist or attempting to decipher the methods of their innovation.

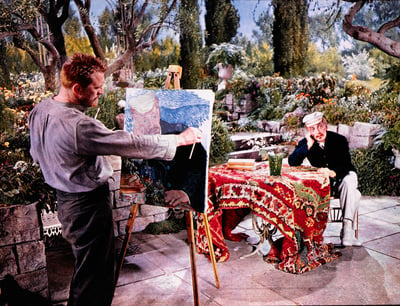

Kirk Douglas plays the unstable Vincent Van Gogh in this Oscar-winning biopic. Emphasising Gogh’s frustration that his technical ability was unable to match the purity of his vision, Douglas employs manic speech and erratic choreography to represent the artist’s creative impulses. The actor has been accused of overstating this performance, and of being too indulgent in his dramatic portrayal of artistic inspiration. One scene in particular comes to mind, in which Douglas is aggressively striking Wheatfield with Crows with his paintbrush, teeth bared, moustache quivering and with a cloud of crows flapping about his head, while a bemused farmer looks on from his cart.

Apparently Douglas prepared for this role by painting cows, so that he could mimic the artist at work. The film documents Van Gogh’s tortured life, from an unrequited love affair to his bout in a psychiatric institution, and suggests that the root of the artist’s creativity was his mental instability.

After being told, ‘with all your talk of emotion, all I see when I look at your work is just that you paint too fast!‘, Vincent replies ‘you look too fast!’

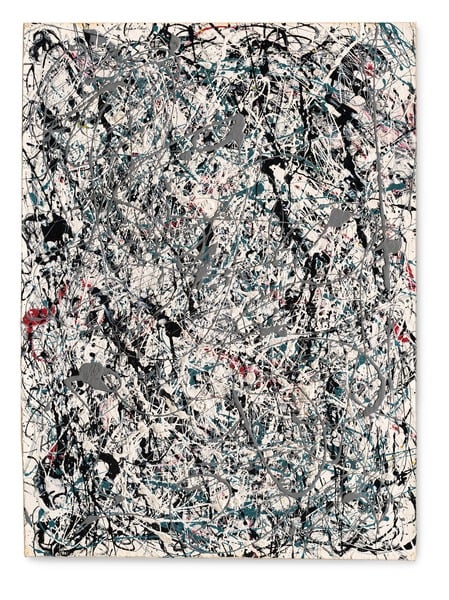

Pollock (2000)

Starring and directed by Ed Harris, this film tracks the career of Jackson Pollock from his breakthrough until his fatal drunken car accident. The biopic had been a decade-long project for Harris, and his philosophy during its making was ‘to do a subtle job. I was not interested in exploring innovative techniques.’ This film doesn’t present a discourse on the mystic power of authentic creative genius, nor is it shy of depicting Pollock’s greed for fame. Harris’ rendering of the artist’s novel methods highlights a physical aspect, crouching over vast canvases and dripping paint mid-stride.

As Pollock said himself, ‘the modern artist [or actor] … is working and expressing an inner world – in other words – expressing the energy, the motion, and other inner forces.‘

Mr Turner (2014)

Timothy Spall plays the eccentric landscape artist J. M. W. Turner, examining the final 25 years of his life. According to director and scriptwriter Mike Leigh’s unconventional production methods, the actors built up their characters through a slow process of improvisation: ‘our job is to invent, not just to be somebody who’s trying to document’ (Spall). Having taken lessons from portrait artist Tim Wright years before filming, Spall was able to illustrate the enigmatic process of the artist, spitting at the canvas and rubbing the paint in order to mimic Turner’s peculiar style.

J. M. W.Turner (1775-1851) at the Royal Academy, Varnishing Day by Parrott, William (1813-69); The Collection of the Guild of St. George, Sheffield, UK

A certain amount of psychological analysis of the man went into trying to recreate his creative perspective, such as the actor’s expressive grunt and stylised hunch: Turner was ‘in a sense implosive in his nature and implosive in his body, but actually explosive in his expression when he comes to his art. It was almost like we were trying to build a character that was sucking everything in so he could shoot it all out’.

Like what you see? Get in touch with your local Bridgeman office for any image research or licensing queries:

North and South America: nysales@bridgemanimages.com