Centenary of the Battle of Messines

The Battle of Messines (1st – 14th June 1917) has been called one of the most successful allied offensives in the First World War, noted for its effective artillery tactics, military communication methods and the speed of its gains. With its hundredth anniversary coming up next month, here is an overview of why it was such an important moment.

In the aftermath of the Battle of the Somme (1st July – 18th November 1916), General Sir Herbert Plumer adopted alternative ‘bite and hold’ tactics in the planning of the Battle of Messines, Flanders. This more conservative approach, in which small advances were made and these positions reinforced, was based on realistic objectives and seemed more sensible than planning to make sweeping gains with huge numbers of troops. The main objective of the offense was to take the strategic stronghold of the Messines ridge, from which the Germans had been observing the movements of Allied troops. This battle was part of the wider goal to break the German front at Ypres.

UIG1583848 British Front, Belgium, 1914 Battle of Messines, 1914 (b/w photo); (add.info.: German soldiers with 10.5cm Light Field Howitzer. Messines, Belgium. 1914. .); Windmill/Robert Hunt Library/UIG; out of copyright

The groundwork began months in advance, with the Allies digging 8,000 m of tunnels under the German lines in order to plant mines for use in the attack. The soldiers also dug in communication trenches, complete with 12,000 m of telephone lines, at least 7ft beneath the predicted Allied positions, making sure that heavy German artillery would not disrupt effective organisation of the battle.

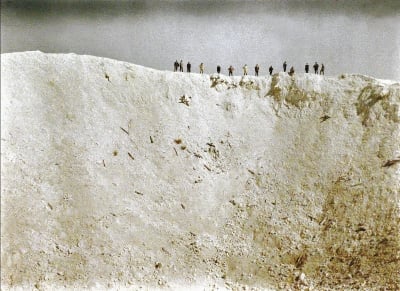

On 7th June, the Allies detonated 19 mines, killing an estimated 10,000 German troops and making the loudest manmade explosion to date. Lloyd George apparently heard it in his study in Downing Street, and the flashing in the sky as the 20-second long explosion series ran was likened to a ‘pillar of fire’.

‘Gentlemen, we may not make history tomorrow but we shall certainly change the geography’, General Plumer remarked to his staff the evening before the attack. Of the 22 mine shafts laid beneath enemy lines, one was detected and disposed of by German counter-miners months prior to the battle, and two others were left unexploded. To the disquiet of locals, the British forces mislaid their information regarding the precise location of these mines. During a thunderstorm on 17th June 1955, one was detonated, killing a cow.

A crater, diameter 116m, depth 45m, following the explosion of 19 mines, ignited by British soldiers under German positions at Messines in West Flanders on 7 June, 1917

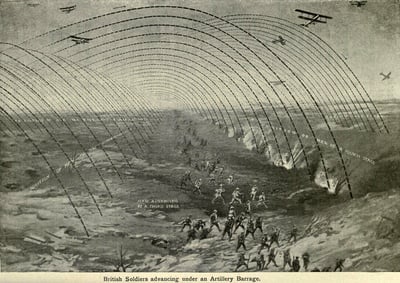

Leaving the German forces no time to recover, the Allied infantry advanced, making use of the ‘creeping barrage’ tactic, in which artillery shells are placed in front of the troops in order to provide a literal smokescreen as protection. After the initial gains had been made, the reserve force moved up with tanks and artillery and repelled the German counter-offenses. The enemy’s artillery, once it had found its range, did inflict numerous casualties on the Allies, and by the end of the battle on 14th June, their casualties are estimated to be around 25,000. While enemy casualties were lighter (at around 22,000), historians largely agree that the offense was a success, costing Germany dearly in morale and reserve forces. Moreover, the taking of the Messines ridge and the subsequent extension of British supply lines is regarded as crucial for the limited success of the Third Battle of Ypres later that year.

World War 1. Diagram of British soldiers advancing under a creeping artillery barrage. Western Front, c. 1915-1918

North and South America: nysales@bridgemanimages.com