Art in the BBC Reith Lectures

In 1948 the BBC established the Reith lectures in honour of the broadcaster’s first director-general, Sir John Reith. Each year leading public figures are invited to deliver a series of radio lectures in their respective fields in order to support Reith’s mission to use the BBC as a national education tool. Famous lectures include Bertrand Russell‘s “Authority and the Individual” and Dr Steve Jones’ “The Language of the Genes”. Here we look at a selection of Reith lectures dedicated to studies in art.

Nickolaus Pevsner: “The Englishness of English Art” (1955)

In these lectures, art historian Nickolaus Pevsner argues that it is necessary to appreciate art from a nationalist point of view. He asks whether there is a definitive English personality, which has affected all artistic production in this country. Has gloomy English weather, for example, taken a distinctive hold on the country’s artists? Would Turner and Constable have had such an interest in foreboding clouds if they had been French?

Off the Nore: Wind and Water, Turner, Joseph Mallord William (1775-1851) / Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, USA

Hampstead Heath, Branch Hill Pond, 1828, Constable, John (1776-1837); Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK

Or in literature, surely the language of a nation affects the way in which its art is perceived? Pevsner takes Shakespeare‘s line ‘It was the nightingale and not the lark’ from Romeo and Juliet, and notes the different tonal effect to its continental counterparts: ‘E ’l usignol—non è la lodola’ (Italian), and ‘Es ist die Nachtigall und nicht die Lerche’ (German).

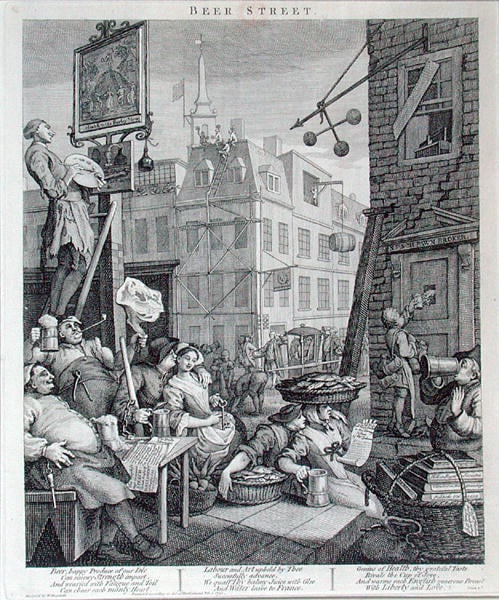

The English have an ’eminently civilised faith in honesty and fair play, the patient queuing […] a certain comfortable wastefulness and sense of a good life’. Yet Pevsner doubted whether these qualities had always been the Anglo-Saxon way. Can we today sympathise with Hogarth‘s debauched view of English revelry, for example?

A Midnight Modern Conversation, from ‘The Works of William Hogarth’, 1733 (engraving) by Hogarth, William (1697-1764); Private Collection

Edgar Wind: “Art and Anarchy” (1960)

Edgar wind examines the political power of art and its ability to galvanise public forces. He turns to Plato‘s suspicion of creative genius, that great evil ‘springs out of a fullness of nature’, such as the sophistic orators which in Plato’s time swayed the armies behind the destruction of Greek city-states, including his own.

School of Athens, from the Stanza della Segnatura, 1510-11 (fresco) (detail of 472), Raphael (1483-1520); Vatican Museums and Galleries, Vatican City

Fortunately, Wind doesn’t argue that Plato’s call for state censorship is necessary today, as art has lost its sting. People today are bombarded by a greater volume of artistic imagery than in any other period, which dilutes the dangerous power of art to motivate the masses. Why not use this an excuse to safely explore the wide variety of images offered by the Bridgeman Images?

Grayson Perry: “Playing to the Gallery” (2013)

Grayson Perry, self-styled ‘foot soldier’ of the modern art world, examines the problem of judging quality in art. The celebrity potter harks back to his predecessors’ attempts to formalise a criteria for judging art, such as Hogarth‘s Serpentine Line of Beauty.

Beer Street, 1751 (engraving) by Hogarth, William (1697-1764), London Metropolitan Archives, City of London, UK

Perhaps financial evaluation provides us with the purest idea of artistic worth, or do the crowds of visitors swarming the Louvre to goggle at the Mona Lisa care more about the price-tag than the artwork itself? Perry is sceptical that an empirical method for judging the quality of an artwork can be found.

The BBC have made the Reith Lectures available to listen to on their website.

Like what you see? Get in touch with your local Bridgeman office for any image research or licensing queries:

North and South America: nysales@bridgemanimages.com