Leonardo da Vinci, the Anatomist

Regarded as one of the greatest artists of the Renaissance and the archetypal polymath, Leonardo da Vinci was also an innovator of anatomical science. In his lifetime, he produced 240 drawings and 13,000 words of notes detailing his discoveries about the human body, which, had they been published, would have fast-tracked the Medical Renaissance. With the 500th anniversary of his death coming up in 2019, here is a brief examination of his impact on the science.

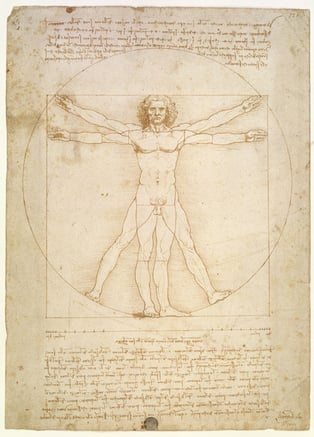

The Proportions of the human figure (after Vitruvius), c.1492 by Vinci, Leonardo da (1452-1519); Galleria dell’ Accademia, Venice, Italy

Described by Sir Kenneth Clark as ‘the most relentlessly curious man in history’, da Vinci developed a fascination with anatomy during his apprenticeship with Andrea del Verrocchio, who encouraged artists to attain a scientific knowledge of the human form. Indeed, an association between anatomy and art was prevalent in his time, and Leonardo’s initial difficulty in obtaining cadavers to study lessened with his commercial success. He was given permission to dissect corpses in the Florentine hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, as well as access to the bodies of executed criminals. Although an interest in examining corpses was frowned upon, and Leonardo was chastised in Rome for his ‘unseemly conduct’, the extent to which the church proscribed the activity is often exaggerated, and at the end of his life Leonardo could boast to having dissected at least 30 bodies.

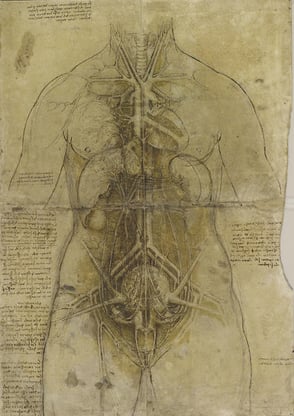

The principal organs and vessels of a woman, c.1510 by Vinci, Leonardo da (1452-1519); Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2017

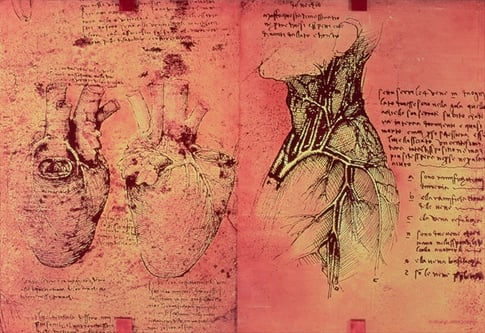

Such an opportunity wasn’t wasted on Leonardo, and during his period of anatomical research he made many important observations, such as the first accurate depiction of the human spine, detailing the skeletal pressures and mechanical functions. Having fashioned a glass model of the aortic valve, Leonardo filled it with water and pumped grass seeds through, taking a crucial step towards understanding the circulatory system. Most importantly perhaps, he realised that the contemporary two-chamber conception of the human heart was incorrect, and that in fact two atrial chambers contracted together while two ventricle chambers relaxed to create a pump action.

Anatomical drawing of hearts and blood vessels, fol. 3v from Quaderni di Anatomia vol. 2, 1499 by Vinci, Leonardo da (1452-1519); Private Collection

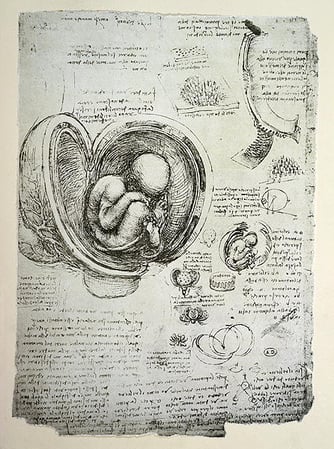

These discoveries are even more remarkable given the debilitating inaccuracies of Renaissance medicine which Leonardo would have had to shake off. For example, he found no place in his understanding of the human anatomy for the prevalent theory of the Four Humours – that the health of a body was dependent on the balance of four internal substances (black bile, yellow bile, phlegm and blood). In other areas, however, Sigmund Freud’s famous phrase rings true, that Leonardo ‘awoke too early in the darkness, while everyone else was still asleep’, so that his potential was limited by the juvenile scientific culture he was born into. His understanding of the human reproductive system was marred by the Dark Age belief that it was similar to that of a plant, as in his mind seeds had an umbilical cord and plants a uterus. In the sketch below da Vinci displays this connection by having the uterus open up like the petals of a flower.

The Human Foetus in the Womb, facsimile copy, by Vinci, Leonardo da (1452-1519) (after); Bibliotheque des Arts Decoratifs, Paris, France

Despite making ground-breaking observations, Leonardo failed to publish his anatomical treatise, leaving the sketches and notes to his assistant Francesco Melzo after his death in 1519, and so his work cannot be claimed to have made any significant impact on the development of Western anatomical science.

Like what you see? Get in touch with your local Bridgeman office for any image research or licensing queries:

North and South America: nysales@bridgemanimages.com