Celebrate Easter: Painting The Passion

Explore the true meaning of Easter shining forth in generations of art

For centuries, artists have depicted the events surrounding Jesus’s crucifixion. Full of emotion and symbolism, these scenes are reminders of the power of artistic expression. Though the earliest paintings of the Crucifixion date from the 5th century, The Passion story was given its first truly artistic outing in Giotto‘s frescoes in the Cappella degli Scrovegni in Padua, Italy between 1303 and 1310.

Lamentation over the Dead Christ, c.1305 (fresco) by Giotto di Bondone (c.1266-1337); Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel, Padua, Italy

In medieval times, art was used as a tool to illustrate church doctrine to the illiterate masses. Stained glass windows, gilt altarpieces and other artistic representations had a narrative, rather than an emotional focus. Giotto was one of the first important artists to break away from this doctrine, pioneering a naturalistic revolution.

Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane/ Barna da Siena / Collegiata; Window of depicting the Crucifixion/ English School / Canterbury Cathedral

The Renaissance brought a far more psychological approach to painting and a focus on capturing facial expression. In addition, many of the Renaissance artists had studied anatomy so their ability to accurately capture the human form was far greater than artists of the medieval period. This was also partly to do with the rise of humanism and the belief that the individual had free will, rather than the course of his life being pre-determined by God.

The 18th and 19th centuries, with Enlightenment theory and later Romanticism focusing on the individual, the sense of art for education or for the community seems to lessen and it appears to become more of an expression of individual belief or feeling. The focus seemed to be on the style of the individual and their personal interpretation, rather than adherence to the overall style of the period.

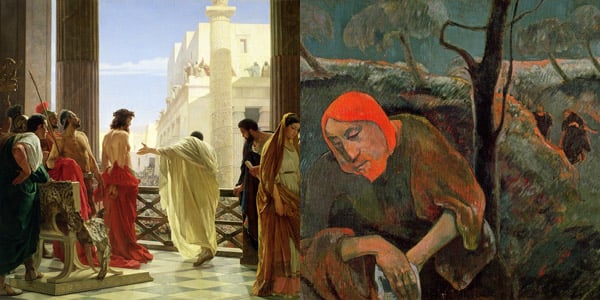

Ecce Homo/ Antonio Ciseri / Galleria d’Arte Moderna; The Agony in the Garden/ Paul Gauguin / Norton Gallery, Florida

Critics have argued that religious art met its zenith in the Renaissance. However, it may just be that the relationship between art and religion in the modern world has become more complicated. Before the internet, television and our insatiable hunger for popular culture, man had a far simpler relationship with his faith; religious paintings of Jesus’s suffering hung in dark churches and had the ability to convey emotion in an immediate and personal way.

Religion still maintains an immense power within the modern art world. Following the 16th century, when autonomy independent from religion did not exist, a sense of faith has become an individual choice rather than an essential element to life. Likewise, the artist’s relationship to the theme of religion has become a far more personal one, a means to work through feelings towards their beliefs as well as the complicated position religion holds within modern life.

Bridgeman holds over 500 images of contemporary Christian art from illustrations of biblical stories, to conceptual religious themes making it clear that a modern understanding of Christianity through art will never conform to a unified standard.

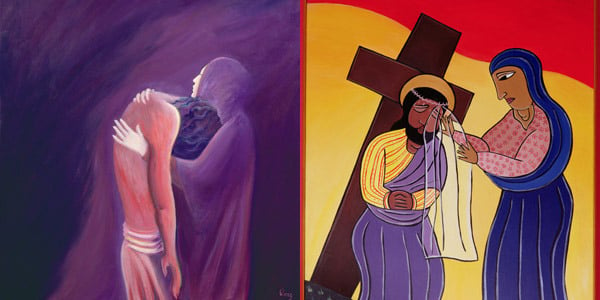

Virgin Mary holds her Son Jesus after His death/ Elizabeth Wang; Jesus and Veronica, no. 6/ Laura James

Find out more:

View more images for the Resurrection

Get in touch with the Bridgeman team on uksales@bridgemanimages.com with enquiries about licensing images and clearing copyright.